12 OOP Concepts EVERY Developer Should Know

Key Object-Oriented Programming Concepts

Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) gives you a practical way to structure software around real-world “things” like Users, Orders, Payments, and Notifications.

Instead of scattering data across variables and wiring behavior through unrelated functions, you bundle state and behavior into self-contained units. That makes code easier to reason about, extend, test, and maintain as the project grows.

But OOP is not just about writing classes. It is about understanding a small set of core ideas that help you model complexity, control change, and avoid turning your codebase into a fragile mess.

In this article, we’ll cover 12 OOP concepts every developer should know, with real-world examples and code. These concepts also appear frequently in low-level design interviews. I’ve also included links to help you explore each concept in more depth.

Lets get started.

Building Blocks

1. Classes

A class is a blueprint that defines the structure and behavior of objects. It specifies what data something will hold (fields) and what actions it can perform (methods).

Real-World Analogy: Think of it like an architectural blueprint for a house. The blueprint specifies the number of rooms, doors, and windows. But you can’t live in a blueprint. You need to build an actual house from it.

public class User {

private String username;

private String email;

private String role;

public User(String username, String email, String role) {

this.username = username;

this.email = email;

this.role = role;

}

public boolean isAdmin() {

return "ADMIN".equals(role);

}

public String getDisplayName() {

return username + " (" + role + ")";

}

}In the above example, the User class bundles username, email, and role together with the methods that operate on them.

But a class by itself doesn’t do anything. It’s just a template. To actually use it, you need to create objects.

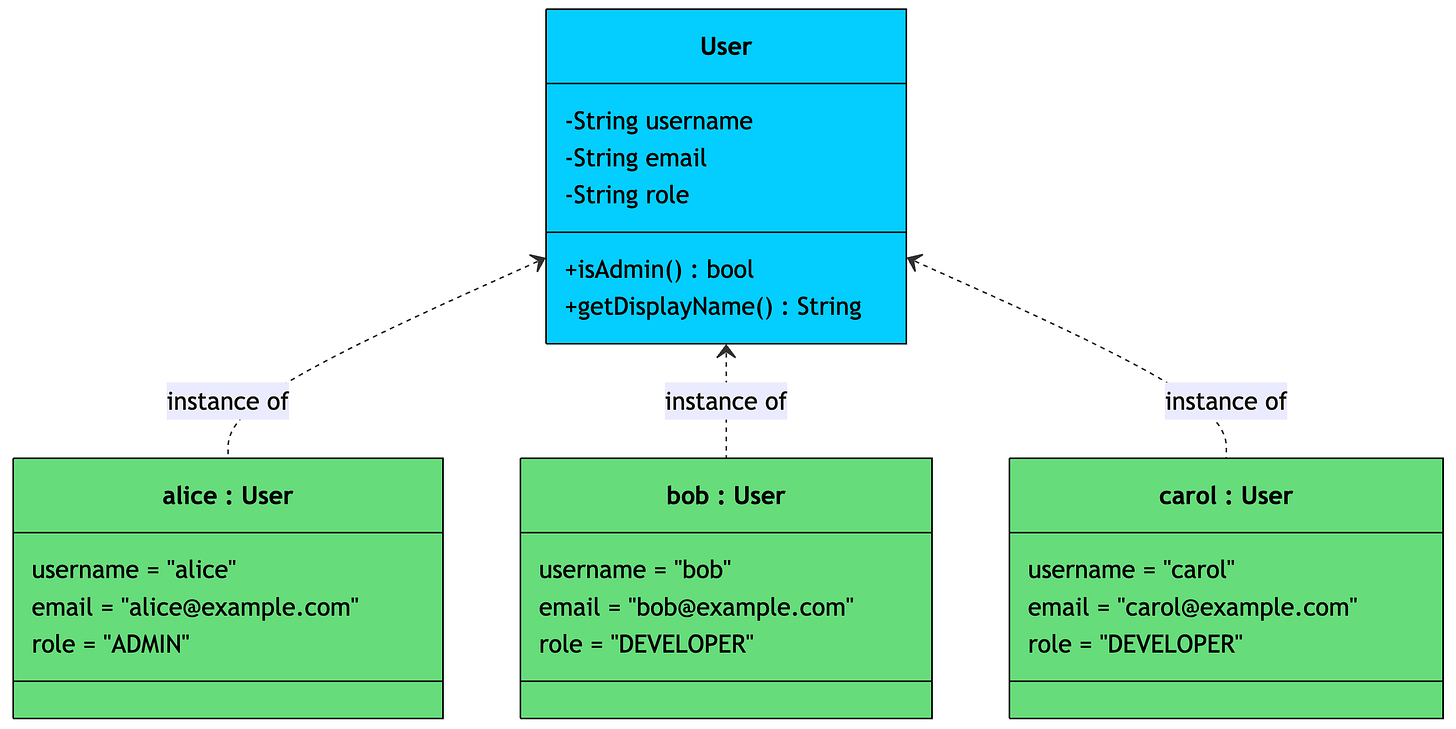

2. Objects

An object is a concrete instance of a class. It has actual values for the fields defined in the class.

If the class is a template, each object is a filled-in copy. You can create many objects from the same class, and each one is independent.

// Creating objects from the User class

User alice = new User("alice", "alice@example.com", "ADMIN");

User bob = new User("bob", "bob@example.com", "DEVELOPER");

User carol = new User("carol", "carol@example.com", "DEVELOPER");

alice.isAdmin(); // true

bob.isAdmin(); // false

alice.getDisplayName(); // alice (ADMIN)Each object has its own copy of the fields. Changing alice‘s role doesn’t affect bob. They’re independent instances built from the same template.

Classes and objects let you group related data and behavior together. But in larger systems, you often need to define what behaviors must exist without specifying how they work. That’s where interfaces come in.

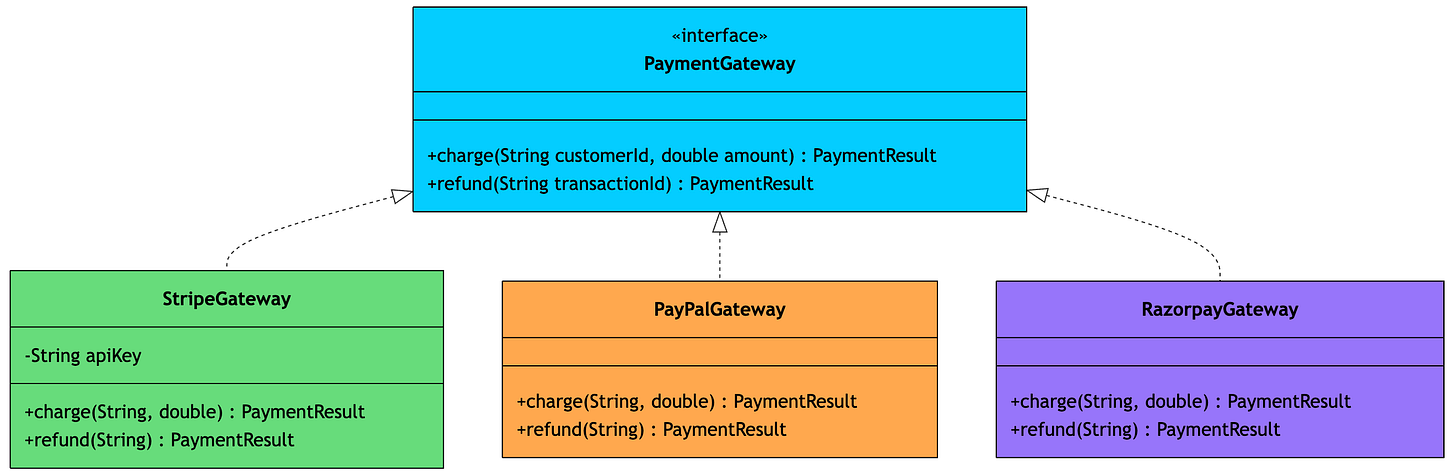

3. Interfaces

An interface is a contract. It defines a set of methods that a class must implement, without specifying how they should work.

Think about payment processing in an e-commerce app. You need to charge customers, but you don’t want to be locked into a single payment provider. So, you define a contract that says “any payment gateway must support charging and refunding,” and then Stripe, PayPal, Razorypay or any future provider can plug in.

public interface PaymentGateway {

PaymentResult charge(String customerId, double amount);

PaymentResult refund(String transactionId);

}

public class StripeGateway implements PaymentGateway {

private String apiKey;

public StripeGateway(String apiKey) {

this.apiKey = apiKey;

}

@Override

public PaymentResult charge(String customerId, double amount) {

// Stripe-specific API call

System.out.println("Charging $" + amount + " via Stripe");

return new PaymentResult(true, "txn_stripe_123");

}

@Override

public PaymentResult refund(String transactionId) {

System.out.println("Refunding " + transactionId + " via Stripe");

return new PaymentResult(true, transactionId);

}

}

public class PayPalGateway implements PaymentGateway {

@Override

public PaymentResult charge(String customerId, double amount) {

// PayPal-specific API call

System.out.println("Charging $" + amount + " via PayPal");

return new PaymentResult(true, "txn_paypal_456");

}

@Override

public PaymentResult refund(String transactionId) {

System.out.println("Refunding " + transactionId + " via PayPal");

return new PaymentResult(true, transactionId);

}

}The beauty of interfaces is that your checkout service can work with PaymentGateway without knowing whether it’s talking to Stripe or PayPal. Swapping providers means changing one line of configuration, not rewriting your business logic.

Interfaces tell you what classes must do. The four pillars of OOP tell you how to design those classes well.

The Four Pillars

4. Encapsulation

Encapsulation is the practice of bundling data and methods together in a class while restricting direct access to the internal data. You expose a controlled public interface and hide everything else.

Consider a rate limiter. Other parts of your system only need to ask “can this user make another request?” They shouldn’t be able to directly mess with the internal counters or reset the time window.

Here’s what happens without encapsulation:

public class RateLimiter {

public int requestCount; // Anyone can modify directly

public long windowStartTime; // Anyone can reset the window

public int maxRequests;

}

RateLimiter limiter = new RateLimiter();

limiter.requestCount = -100; // Invalid state

limiter.windowStartTime = 0; // Window brokenAnd with encapsulation:

public class RateLimiter {

private int requestCount;

private long windowStartTime;

private final int maxRequests;

private final long windowSizeMs;

public RateLimiter(int maxRequests, long windowSizeMs) {

this.maxRequests = maxRequests;

this.windowSizeMs = windowSizeMs;

this.windowStartTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

this.requestCount = 0;

}

public boolean allowRequest() {

resetWindowIfExpired();

if (requestCount < maxRequests) {

requestCount++;

return true;

}

return false;

}

public int getRemainingRequests() {

resetWindowIfExpired();

return maxRequests - requestCount;

}

private void resetWindowIfExpired() {

long now = System.currentTimeMillis();

if (now - windowStartTime >= windowSizeMs) {

requestCount = 0;

windowStartTime = now;

}

}

}Now nobody can corrupt the internal state. The only way to interact with the limiter is through allowRequest() and getRemainingRequests(). The window-reset logic is completely internal. If you later switch from a fixed window to a sliding window algorithm, none of the calling code needs to change.

Encapsulation hides a class’s internal data. But there’s a closely related concept that hides complexity at a higher level.

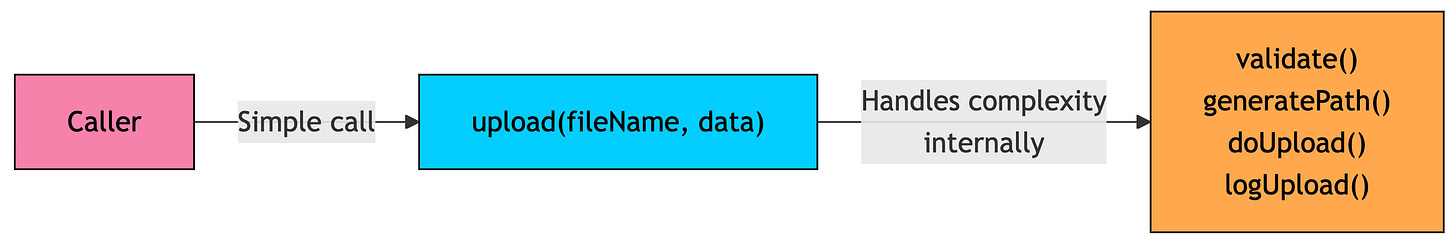

5. Abstraction

Abstraction is about hiding unnecessary complexity and exposing only what the user needs. While encapsulation hides data, abstraction hides implementation details.

Real-World Analogy: Think about sending a message through Slack. You type a message and hit send. Behind the scenes, there’s WebSocket management, message serialization, retry logic, delivery confirmation, and push notifications. You don’t deal with any of that. The complexity is abstracted away behind a simple action.

In code, abstraction typically uses abstract classes or interfaces to define simplified interactions:

public abstract class CloudStorage {

// What the caller sees - one simple method

public String upload(String fileName, byte[] data) {

validate(fileName, data);

String path = generatePath(fileName);

String url = doUpload(path, data);

logUpload(fileName, url);

return url;

}

// Each provider implements its own upload logic

protected abstract String doUpload(String path, byte[] data);

private void validate(String fileName, byte[] data) {

if (fileName == null || data.length == 0) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Invalid file");

}

}

private String generatePath(String fileName) {

return "uploads/" + System.currentTimeMillis() + "/" + fileName;

}

private void logUpload(String fileName, String url) {

System.out.println("Uploaded " + fileName + " to " + url);

}

}

public class S3Storage extends CloudStorage {

@Override

protected String doUpload(String path, byte[] data) {

// AWS SDK calls, multipart upload, encryption...

return "https://s3.amazonaws.com/bucket/" + path;

}

}

public class GcsStorage extends CloudStorage {

@Override

protected String doUpload(String path, byte[] data) {

// Google Cloud SDK calls, resumable upload...

return "https://storage.googleapis.com/bucket/" + path;

}

}The caller just invokes upload(). They don’t need to know about path generation, validation, or provider-specific SDK calls. All that complexity is abstracted away.

Abstraction simplifies how you interact with objects. But what if multiple classes share the same data and behavior? That’s where inheritance steps in.

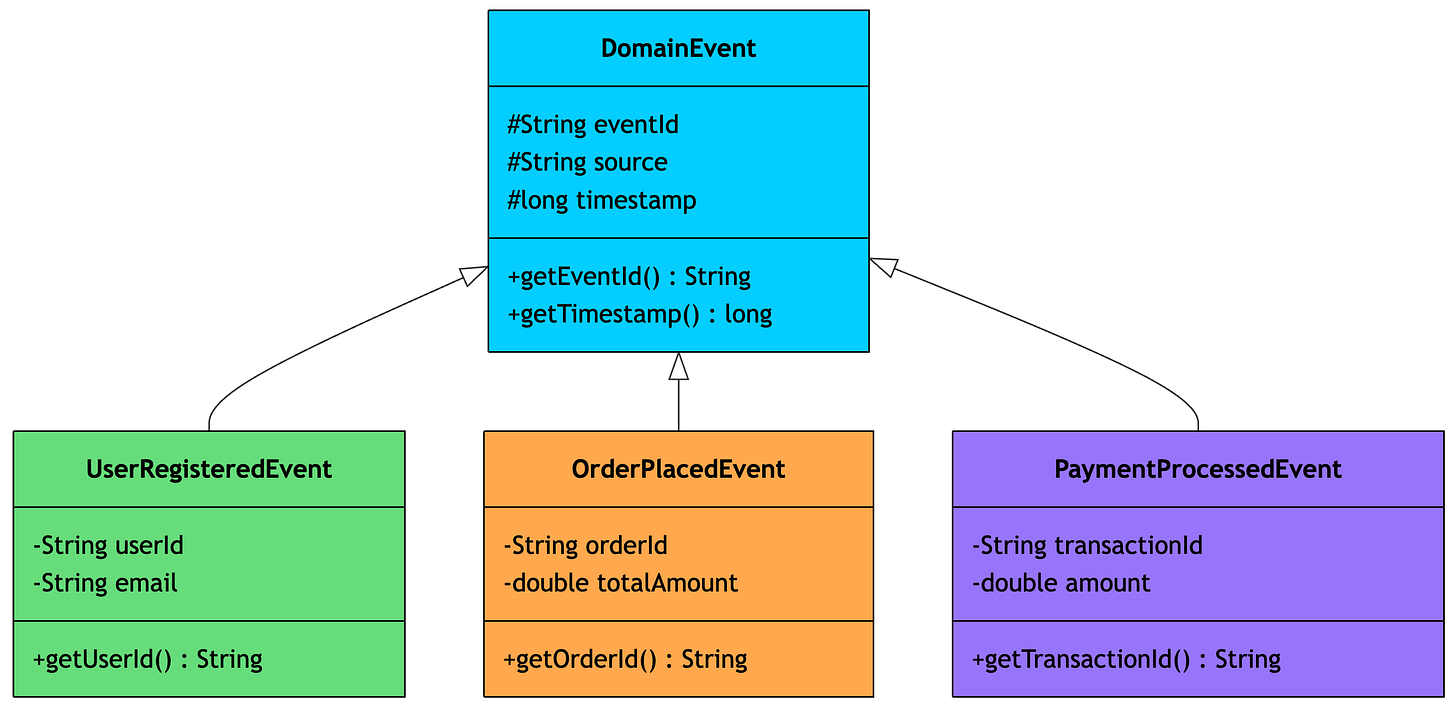

6. Inheritance

Inheritance lets a new class (child) derive from an existing class (parent), inheriting its fields and methods. The child class can reuse the parent’s code, add new behavior, or override existing behavior.

In an event-driven system, every event needs a timestamp, an event ID, and a source. But each specific event type carries its own payload. Instead of duplicating the common fields in every event class, you define them once in a base class.

public class DomainEvent {

protected String eventId;

protected String source;

protected long timestamp;

public DomainEvent(String source) {

this.eventId = UUID.randomUUID().toString();

this.source = source;

this.timestamp = System.currentTimeMillis();

}

public String getEventId() {

return eventId;

}

public long getTimestamp() {

return timestamp;

}

}

public class UserRegisteredEvent extends DomainEvent {

private String userId;

private String email;

public UserRegisteredEvent(String userId, String email) {

super("user-service");

this.userId = userId;

this.email = email;

}

public String getUserId() {

return userId;

}

}

public class OrderPlacedEvent extends DomainEvent {

private String orderId;

private double totalAmount;

public OrderPlacedEvent(String orderId, double totalAmount) {

super("order-service");

this.orderId = orderId;

this.totalAmount = totalAmount;

}

public String getOrderId() {

return orderId;

}

}UserRegisteredEvent and OrderPlacedEvent both get eventId, source, timestamp, and getEventId() from DomainEvent without writing that code again. They also add their own unique fields.

Use inheritance when there’s a clear “is-a” relationship. A UserRegisteredEvent is a DomainEvent. A StripeGateway is a PaymentGateway. Avoid inheriting just to reuse code. If there’s no natural “is-a” relationship, use composition instead.

Inheritance lets classes share structure and behavior. But what happens when you call the same method on different child classes and get different results?

That’s polymorphism.

7. Polymorphism

Polymorphism means “many forms.” It allows objects of different types to be treated through a common interface, with each type providing its own behavior.

There are two types:

Compile-time (method overloading): same method name, different parameters

Runtime (method overriding): same method signature, different implementations in child classes

Runtime polymorphism is the more powerful concept. Imagine a notification system that sends alerts through different channels:

public interface NotificationChannel {

void send(String recipient, String message);

}

public class EmailChannel implements NotificationChannel {

@Override

public void send(String recipient, String message) {

// SMTP setup, HTML formatting, attachment handling...

System.out.println("Email to " + recipient + ": " + message);

}

}

public class SlackChannel implements NotificationChannel {

@Override

public void send(String recipient, String message) {

// Slack API call, channel lookup, markdown formatting...

System.out.println("Slack to #" + recipient + ": " + message);

}

}

public class SmsChannel implements NotificationChannel {

@Override

public void send(String recipient, String message) {

// Twilio API, phone number validation, character limits...

System.out.println("SMS to " + recipient + ": " + message);

}

}

// Polymorphism in action

List<NotificationChannel> channels = List.of(

new EmailChannel(), new SlackChannel(), new SmsChannel()

);

for (NotificationChannel channel : channels) {

channel.send("ops-team", "Server CPU above 90%");

// Each channel sends the alert its own way

}The loop doesn’t know or care whether it’s sending an email, a Slack message, or an SMS. It calls send() on each one, and the right implementation runs automatically. If you add a PagerDutyChannel tomorrow, the loop works without any changes.

This is the real power of polymorphism: you can write code that works with abstractions, and it automatically handles new types as they’re added.

Now that we understand how individual classes are structured and designed, let’s look at how objects relate to each other.

Object Relationships

8. Association

Association represents a “knows-about” relationship between objects. Both objects exist independently. Neither owns or controls the other.

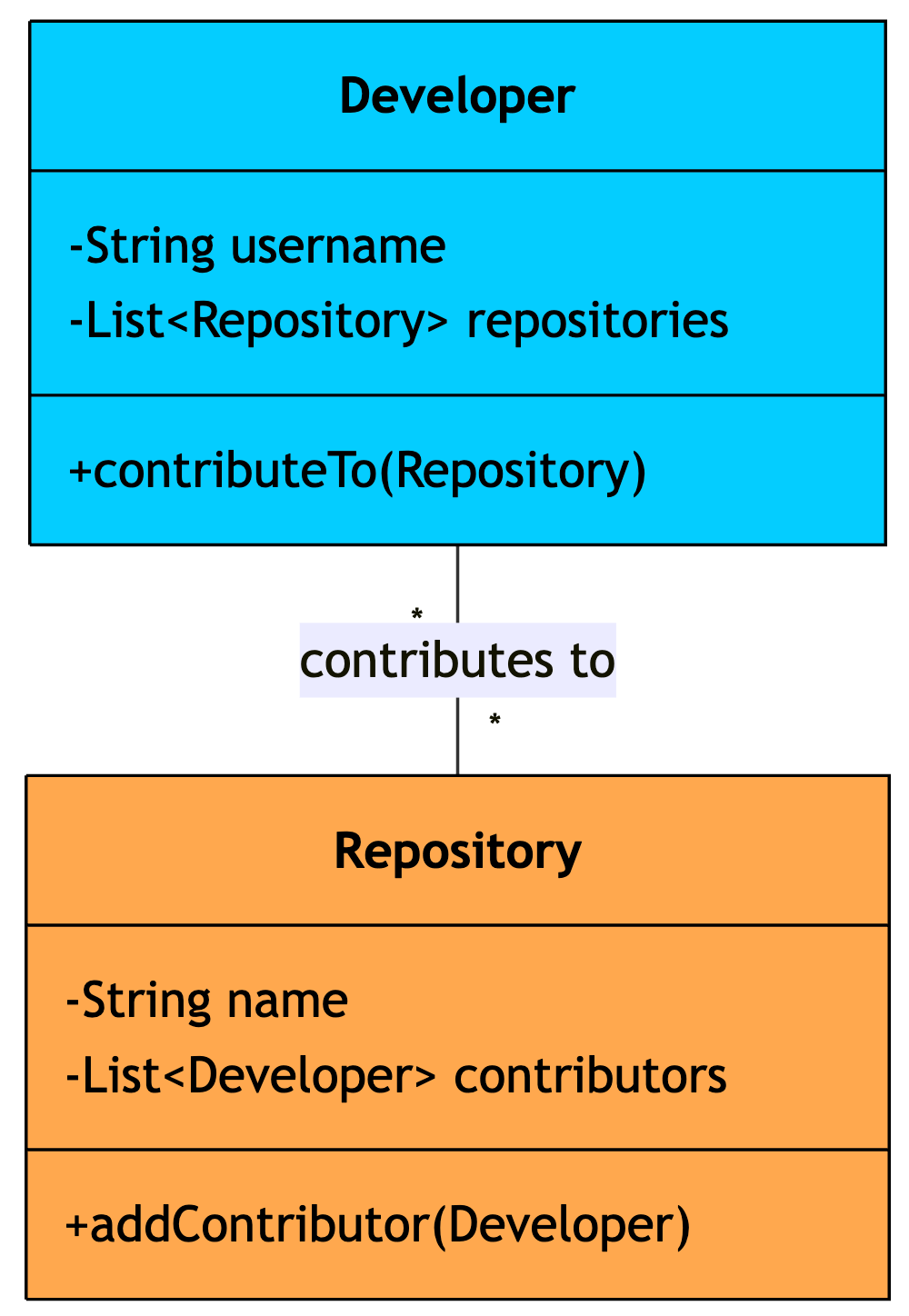

Think of a developer and a repository on GitHub. A developer contributes to multiple repositories, and a repository has multiple contributors. But if a developer deletes their account, the repository still exists. And if a repository is archived, the developer keeps working on other things.

public class Developer {

private String username;

private List<Repository> repositories;

public Developer(String username) {

this.username = username;

this.repositories = new ArrayList<>();

}

public void contributeTo(Repository repo) {

repositories.add(repo);

}

}

public class Repository {

private String name;

private List<Developer> contributors;

public Repository(String name) {

this.name = name;

this.contributors = new ArrayList<>();

}

public void addContributor(Developer dev) {

contributors.add(dev);

}

}

// Both objects are created independently

Developer dev = new Developer("alice");

Repository repo = new Repository("payment-service");

// They reference each other, but neither owns the other

dev.contributeTo(repo);

repo.addContributor(dev);The key here is independence. Both Developer and Repository are created outside of each other and just hold references. Deleting one doesn’t affect the other.

Association is the most general type of relationship. But sometimes, one object is part of another. That brings us to aggregation.

9. Aggregation

Aggregation is a specialized form of association that represents a “has-a” relationship where the whole contains parts, but the parts can exist independently.

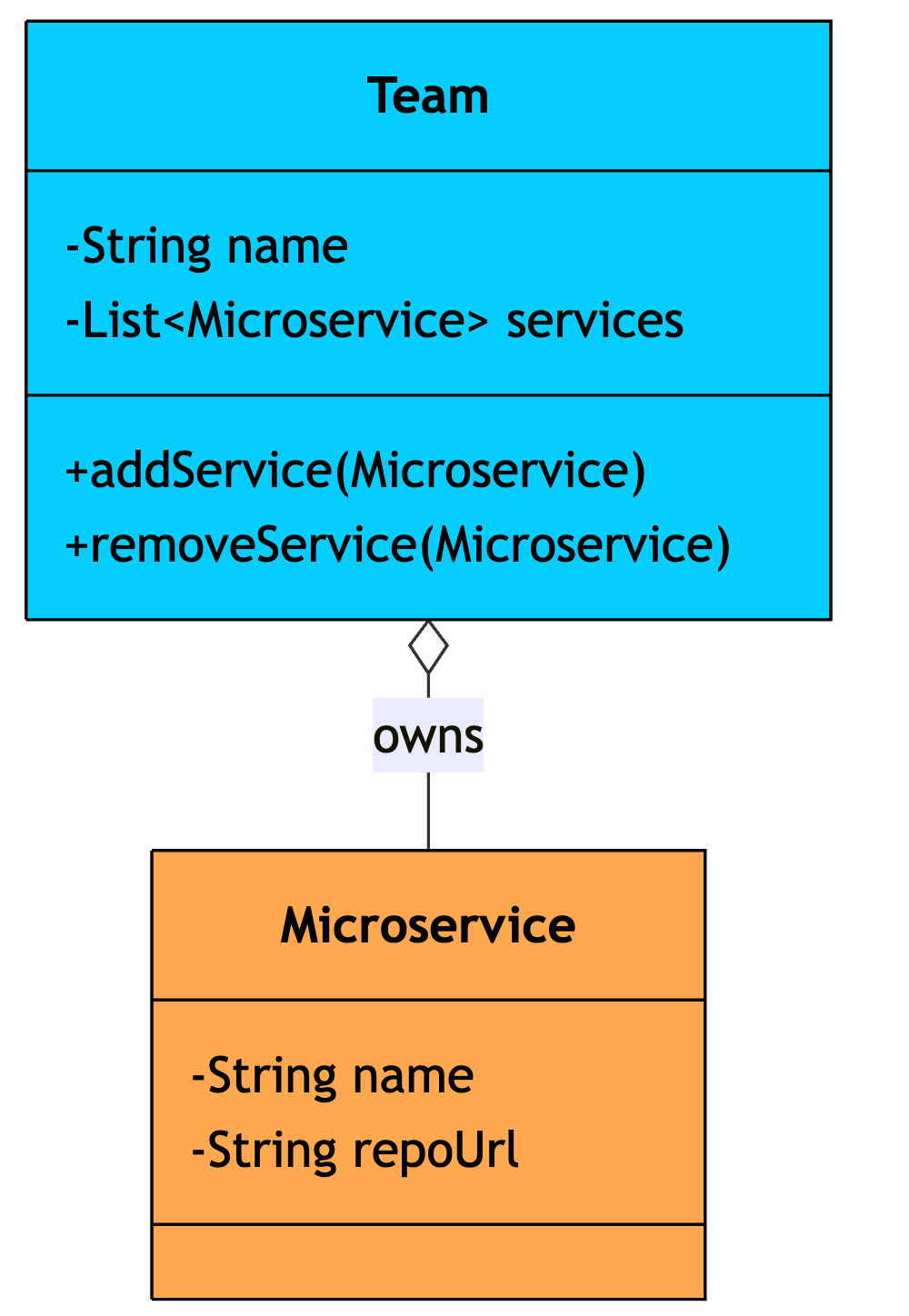

Think of a team and its microservices. A team owns multiple microservices, but if the team is reorganized, the services don’t disappear. They get reassigned to a different team.

public class Team {

private String name;

private List<Microservice> services;

public Team(String name) {

this.name = name;

this.services = new ArrayList<>();

}

// Services are created outside and assigned to the team

public void addService(Microservice service) {

services.add(service);

}

public void removeService(Microservice service) {

services.remove(service);

}

}

public class Microservice {

private String name;

private String repoUrl;

public Microservice(String name, String repoUrl) {

this.name = name;

this.repoUrl = repoUrl;

}

}

// Microservice exists independently

Microservice paymentService = new Microservice("payment-service", "github.com/org/payments");

// Team references the service but doesn't own it

Team platformTeam = new Team("Platform");

platformTeam.addService(paymentService);

// Service can be reassigned to another team

Team checkoutTeam = new Team("Checkout");

checkoutTeam.addService(paymentService);The team has services, but services have their own lifecycle. They exist before being assigned to a team and continue to exist after being reassigned.

In aggregation, parts can survive without the whole. But what if the parts are so tightly coupled to the whole that they shouldn’t exist independently?

That’s composition.

10. Composition

Composition is a strong form of “has-a” where the whole owns the parts entirely. When the whole is destroyed, the parts are destroyed with it. The parts have no meaning outside of the whole.

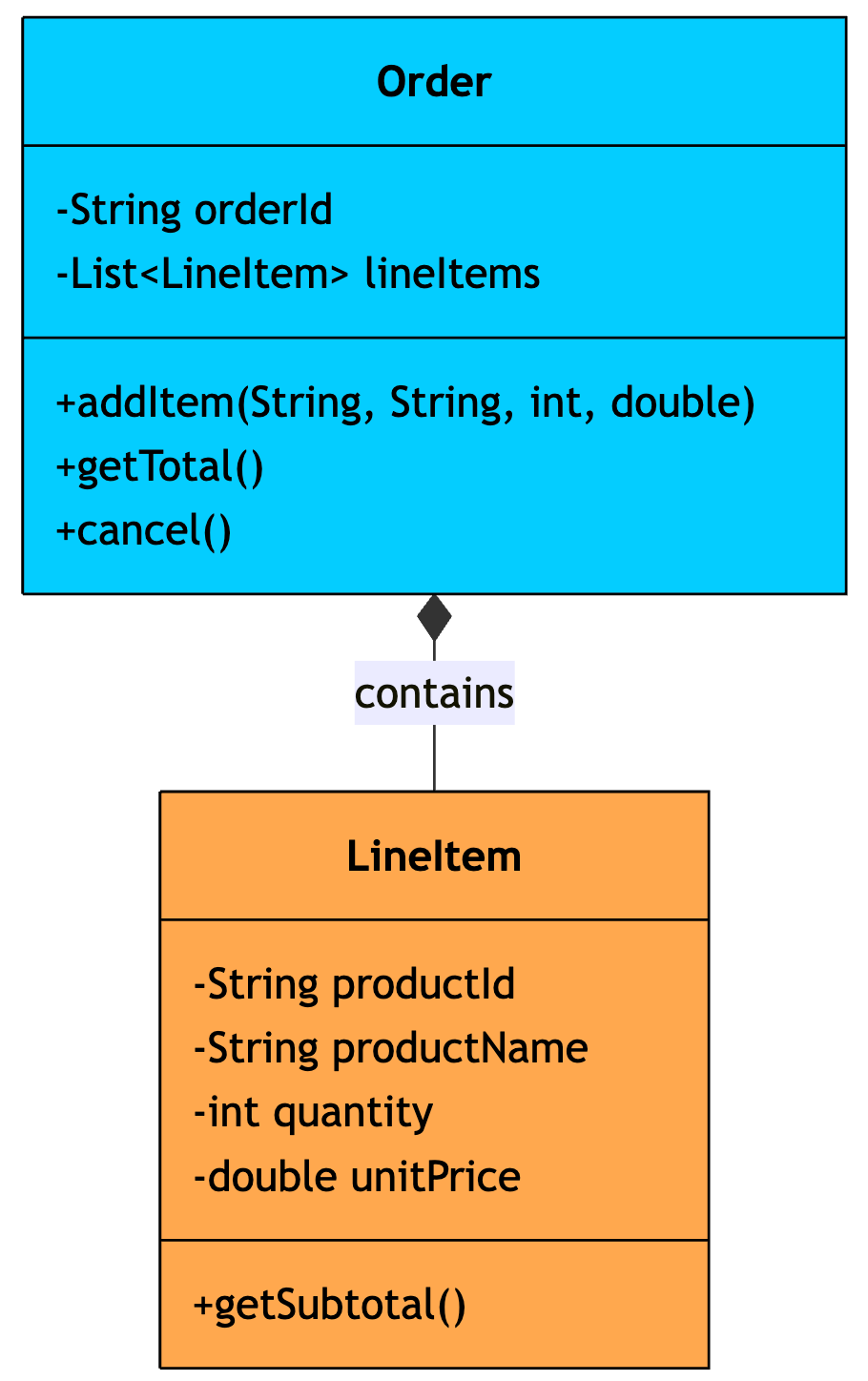

Think of an order and its line items. Each line item (2x T-Shirt, 1x Laptop) only exists as part of that specific order. If the order is cancelled and deleted, the line items go with it. A line item floating around without an order makes no sense.

public class Order {

private String orderId;

private List<LineItem> lineItems; // Order creates and owns line items

public Order(String orderId) {

this.orderId = orderId;

this.lineItems = new ArrayList<>();

}

// Order creates the line item internally

public void addItem(String productId, String productName, int quantity, double price) {

lineItems.add(new LineItem(productId, productName, quantity, price));

}

public double getTotal() {

return lineItems.stream()

.mapToDouble(LineItem::getSubtotal)

.sum();

}

public void cancel() {

lineItems.clear(); // Line items destroyed with the order

System.out.println("Order " + orderId + " cancelled");

}

}

public class LineItem {

private String productId;

private String productName;

private int quantity;

private double unitPrice;

// Package-private: only Order should create line items

LineItem(String productId, String productName, int quantity, double unitPrice) {

this.productId = productId;

this.productName = productName;

this.quantity = quantity;

this.unitPrice = unitPrice;

}

double getSubtotal() {

return quantity * unitPrice;

}

}

// Order creates line items internally - they don't exist outside

Order order = new Order("ORD-001");

order.addItem("SKU-100", "Mechanical Keyboard", 1, 149.99);

order.addItem("SKU-200", "USB-C Hub", 2, 39.99);

System.out.println(order.getTotal()); // 229.97

order.cancel(); // All line items destroyedNotice the difference from aggregation: in composition, the whole creates its parts internally (new LineItem(...) inside addItem). In aggregation, parts are passed in from outside.

Composition is about ownership and lifecycle control. But not all relationships involve ownership. Sometimes one object just temporarily uses another.

That’s dependency.

11. Dependency

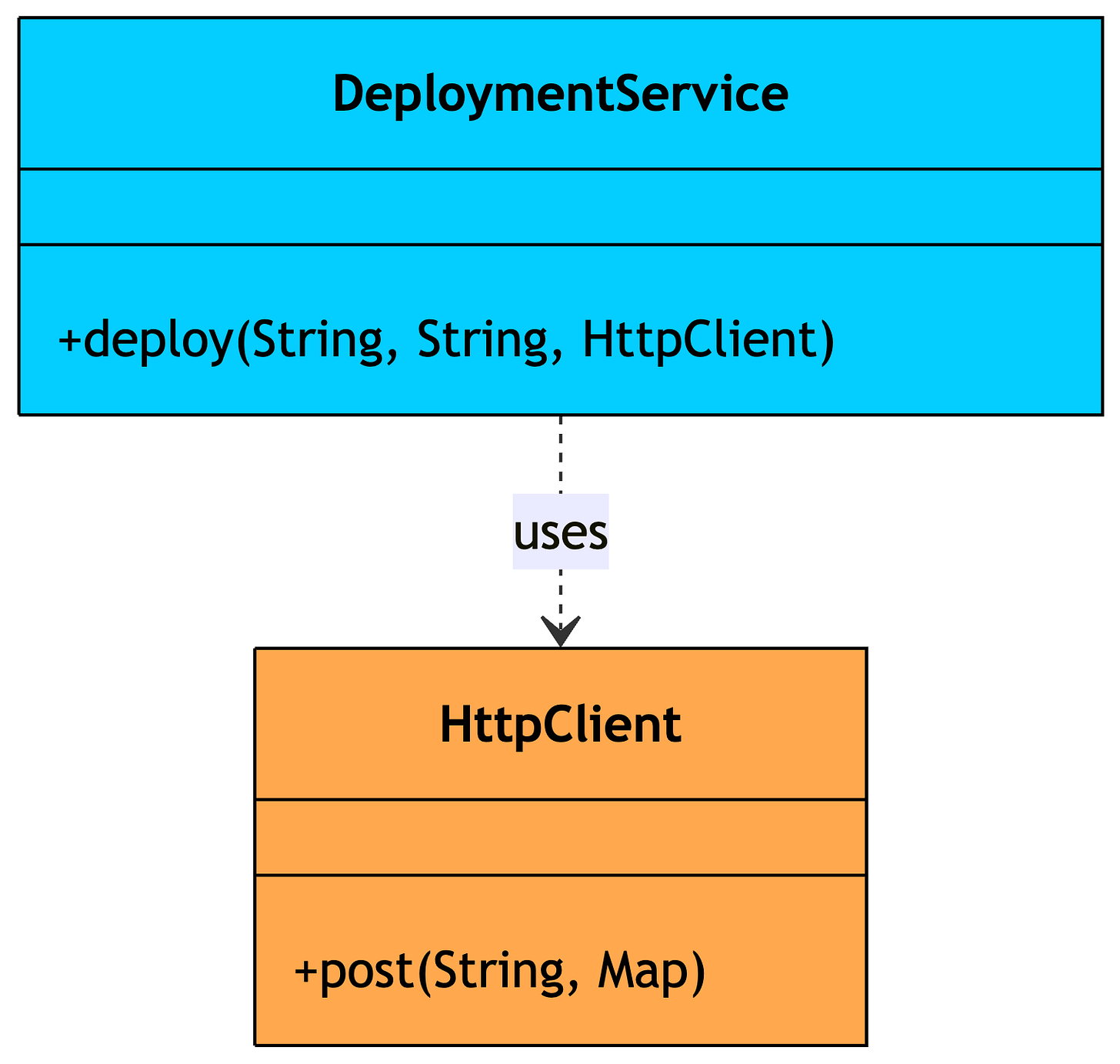

Dependency is the weakest relationship between classes. It represents a temporary “uses-a” connection where one class uses another, typically as a method parameter, local variable, or return type, but doesn’t hold a long-term reference to it.

Think of a deployment pipeline. The pipeline uses a logger to record what’s happening, but it doesn’t own the logger or keep it around as part of its state. It just uses it during execution and moves on.

public class DeploymentService {

// Dependency: uses HttpClient temporarily, doesn't store it

public DeploymentResult deploy(String serviceName, String version, HttpClient client) {

String url = "https://deploy.internal/" + serviceName;

HttpResponse response = client.post(url, Map.of("version", version));

if (response.getStatusCode() == 200) {

return new DeploymentResult(true, "Deployed " + serviceName + " v" + version);

}

return new DeploymentResult(false, "Deployment failed: " + response.getBody());

}

}

public class HttpClient {

public HttpResponse post(String url, Map<String, String> body) {

// HTTP connection setup, request serialization, TLS...

System.out.println("POST " + url);

return new HttpResponse(200, "OK");

}

}

// DeploymentService uses HttpClient but doesn't own or store it

DeploymentService deployer = new DeploymentService();

HttpClient client = new HttpClient();

deployer.deploy("payment-service", "2.4.1", client);DeploymentService depends on HttpClient, but only during the deploy() call. It doesn’t store the client as a field. Once the method returns, the relationship is gone.

Dependency is the weakest of the object relationships. The last concept in our list brings us full circle, connecting interfaces back to the classes that implement them.

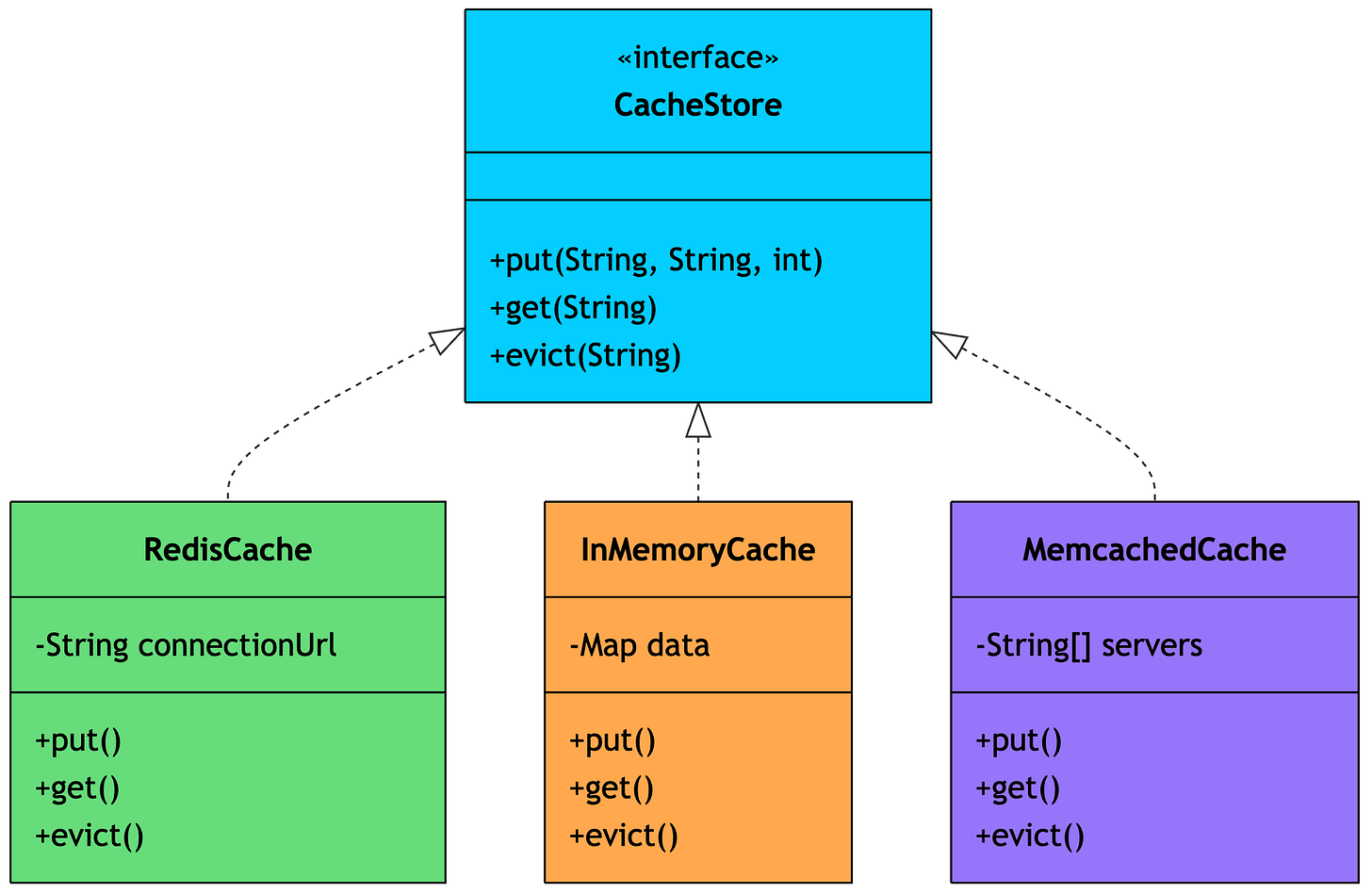

12. Realization

Realization is the relationship between an interface and the class that implements it. The class “realizes” the contract defined by the interface by providing concrete implementations of all its methods.

We already saw this with PaymentGateway in the interfaces section. Let’s look at another example, a cache store:

public interface CacheStore {

void put(String key, String value, int ttlSeconds);

String get(String key);

void evict(String key);

}

public class RedisCache implements CacheStore {

private String connectionUrl;

public RedisCache(String connectionUrl) {

this.connectionUrl = connectionUrl;

}

@Override

public void put(String key, String value, int ttlSeconds) {

// Redis SETEX command with TTL

System.out.println("Redis SET " + key + " EX " + ttlSeconds);

}

@Override

public String get(String key) {

// Redis GET command

System.out.println("Redis GET " + key);

return null; // Simplified

}

@Override

public void evict(String key) {

// Redis DEL command

System.out.println("Redis DEL " + key);

}

}Each class promises to fulfill the CacheStore contract. Your application code depends on CacheStore, so you can use Redis in production, an in-memory map in tests, and Memcached in a different environment, all without changing a single line of business logic.

Realization is what makes polymorphism through interfaces possible. It’s the bridge between abstract contracts and concrete behavior.

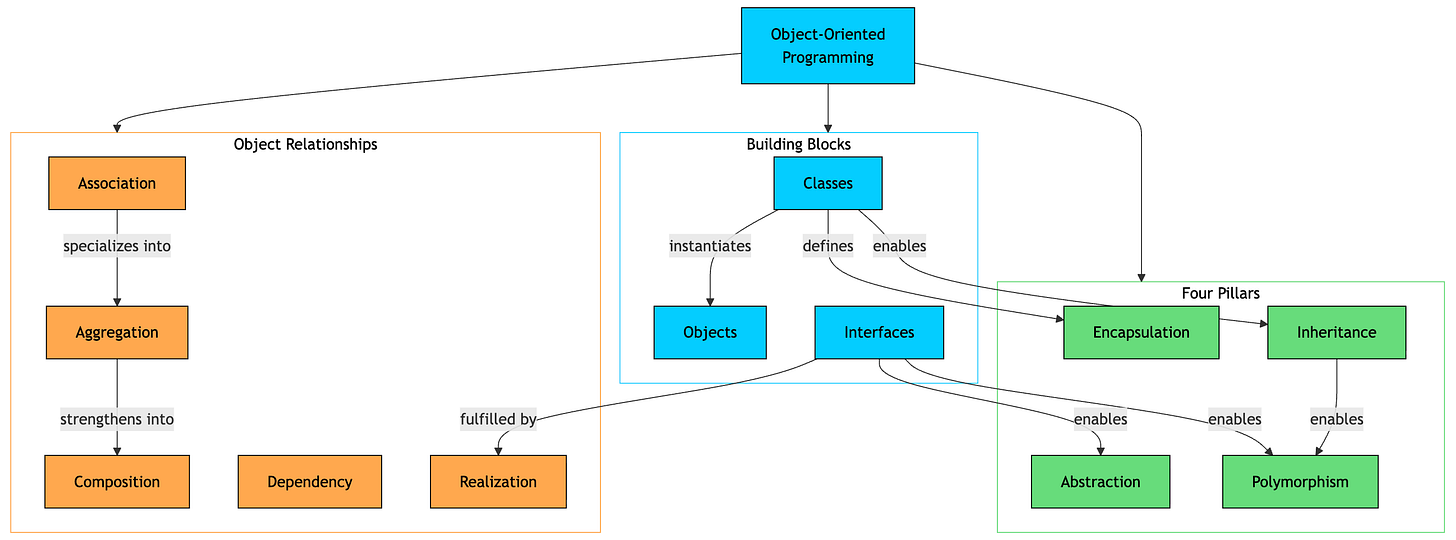

The Big Picture

Here’s how all 12 concepts relate to each other:

These 12 concepts form the foundation of object-oriented design. You don’t need to use all of them in every project, but understanding each one and knowing when to apply it will make you a better software engineer and help you tackle Low-Level Design interviews with confidence.

Thank you for reading!

If you found it valuable, hit a like ❤️ and consider subscribing for more such content every week.

If you have any questions/suggestions, feel free to leave a comment.

One thing that is often missed when considering objects is that they don't have to contain code.

Objects contribute to "strong typing" which reduces bugs and makes them easier to find, and "data objects" (objects without code, designed solely to store data) can extend this to a much lower level inside your code.

Simple code additions can also help with hold the data in a strict format whilst formatting it in different ways for different uses.

And by making classes readonly you can implement immutability which can also reduce bugs.

Finally, use of "final" should be discussed as a way to distinguish between polymorphism base-classes which can be extended (e.g. animal, mammal) , and end-classes which can't (e.g. Tabby Domestic Cat).

Nostalgic to read this! @Ashish Pratap Singh what is your perspective on how oops should be reflected on in the vibe coding era.