How Git Works Internally

A Deep Dive

Most of us treat Git like a black box: memorize a few commands like git add, git commit, and git push, copy-paste the rest, and hope nothing breaks.

But what actually happens when you run these commands? Where do your files go?How does Git track every change you have ever made without consuming gigabytes of storage?

Understanding Git’s internals helps you reason about your changes, debug issues faster, and use Git as the powerful tool it was designed to be.

In this article, we will explore:

What Git really is under the hood

Git’s object model: blobs, trees, and commits

How Git uses SHA-1 hashes to store and address data

The three areas: working directory, staging area, and repository

How commits, branches, merges and rebases actually work

How Git keeps repositories small

1. Distributed Version Control

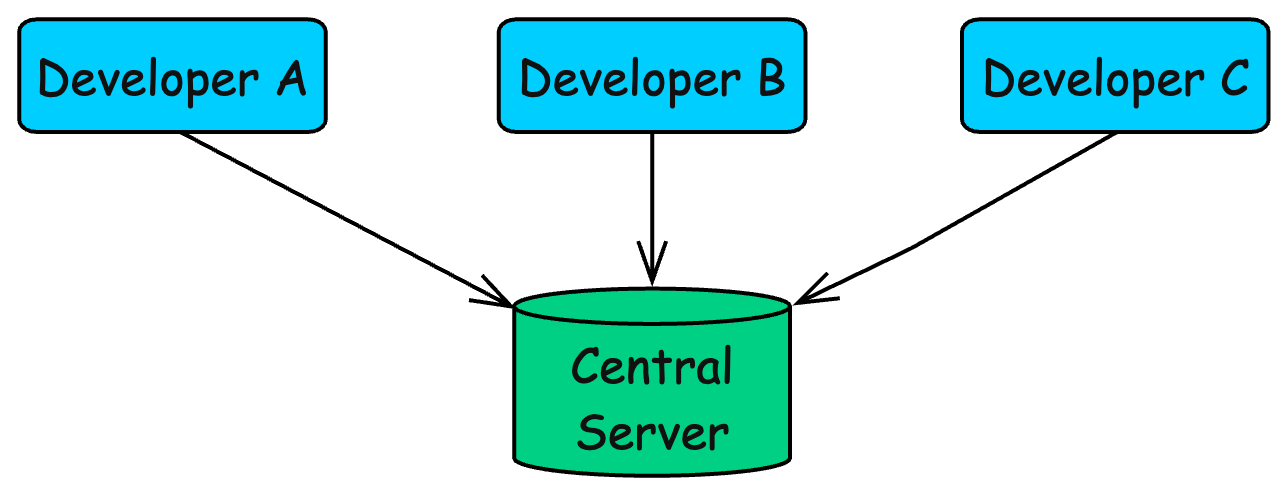

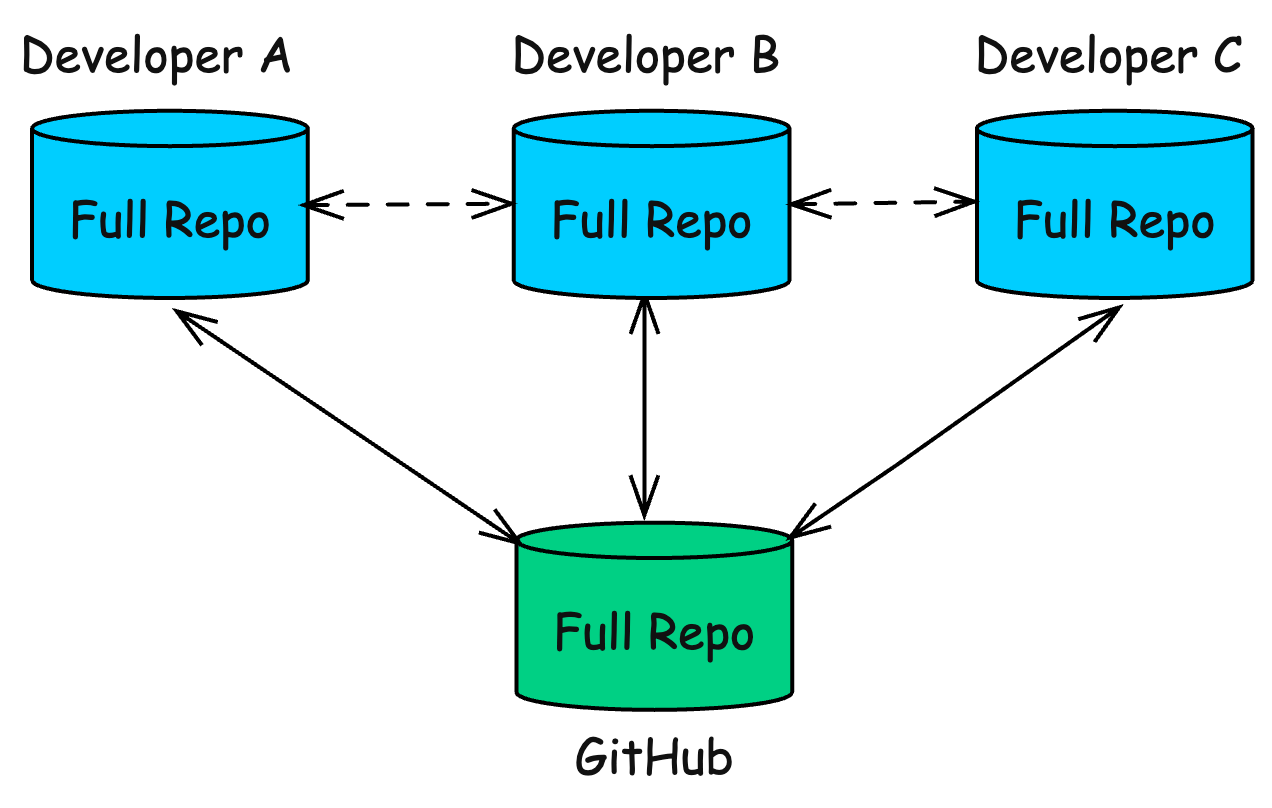

Git is a distributed version control system created by Linus Torvalds in 2005 for Linux kernel development.

Older tools like CVS and SVN use a centralized model: one server holds the source of truth, and developers pull from and push to that central machine.

Git flips this model. In Git, every developer has a full copy of the repository, including the entire history.

This distributed setup gives Git a few key advantages:

Work offline with full history

No single point of failure

Faster operations because most work happens locally

Flexible workflows for teams and individuals

But how does Git store the full history without the repo becoming huge? To answer that, you need to understand the Git’s data model.

2. Git’s Data Model

At its core, Git is a content-addressable filesystem. It stores data as objects, and each object is identified by a SHA-1 hash of its contents.

When you add a file to Git, it computes a 40-character hexadecimal SHA-1 hash of the file’s contents. This hash becomes the file’s unique address in Git’s database.

File contents: "Hello, World!"

SHA-1 hash: 5dd01c177f5d7d1be5346a5bc18a569a7410c2efSame content always produces the same hash. So two files with identical contents (even if they have different names) share the same hash.

Git stores the content once and references it multiple times, which helps repositories stay compact even across thousands of commits.

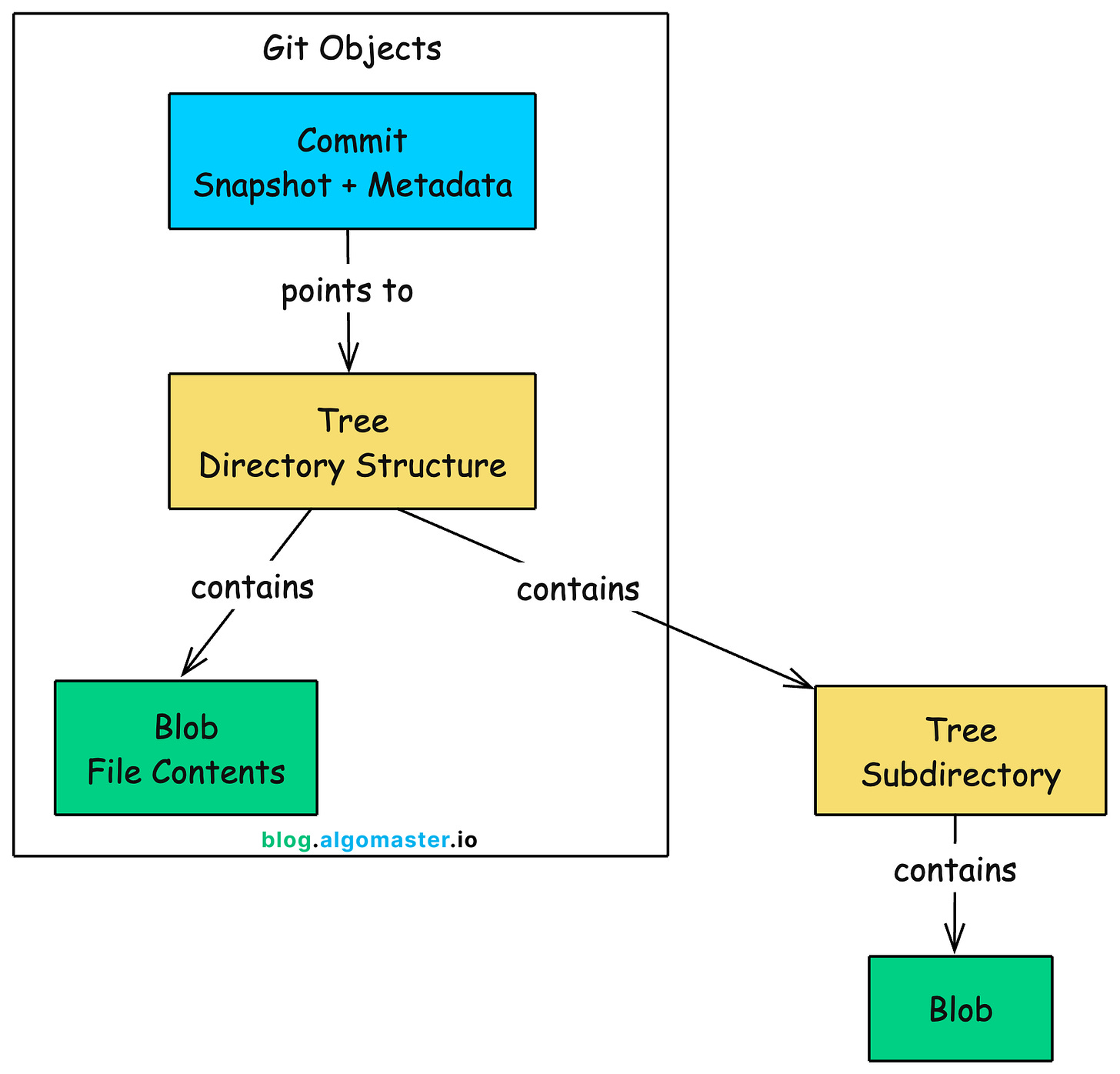

Git organizes everything into objects stored in its database. There are four types of objects, but three are essential for understanding how Git works: blobs, trees, and commits.

Blobs: Storing File Contents

A blob (binary large object) stores the raw contents of a file. Just the contents. No filename, no permissions, no timestamps, no metadata of any kind.

When you add README.md to Git, it creates a blob containing the file’s text. That blob has no idea it came from a file called README.md. It is simply a chunk of bytes with a SHA-1 hash computed from those bytes.

Why separate content from filename?

If the same config file is copied to three locations, a naive system stores three copies. Git stores one blob and references it three times, and these storage savings compound across the project’s history.

Of course, if blobs do not store filenames, Git still needs a way to represent folder structure. That is the job of trees.

Trees: Mapping Directory Structure

A tree represents a directory. It contains pointers to blobs (files) and other trees (subdirectories), along with filenames and permissions.

Tree: 4c5f8a2b9d3e7f1a6b0c8d5e2f9a4b7c3d6e0f1a

├── README.md -> blob 5dd01c17... (100644)

├── src/ -> tree 8a3b2c1d...

└── package.json -> blob 7f2e3d4c... (100644)The tree acts as a directory listing. It says “there is a file called README.md, and its contents are stored in blob 5dd01c17.” The blob stores the data; the tree gives it a name and location.

If you rename a file without changing its contents, Git creates a new tree (with the new filename) pointing to the same blob. The actual file data is not duplicated.

Now we have blobs for content and trees for structure. But version control needs more: who made changes, when, and why. That is what commits provide.

Commits: Recording History

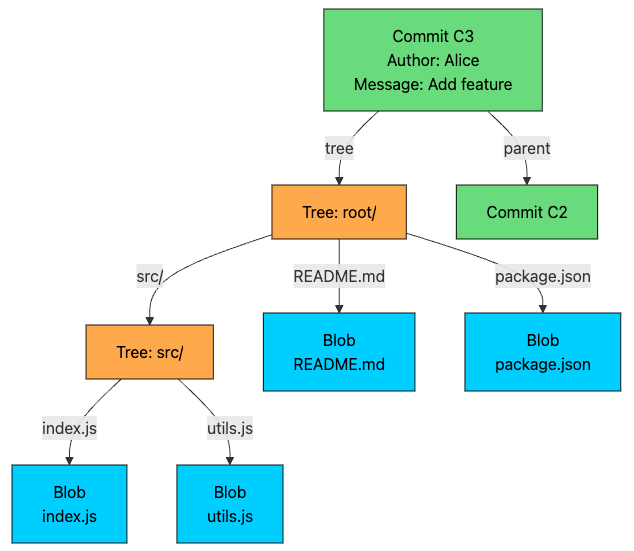

A commit captures a complete snapshot of your project at a specific moment in time. Every commit contains:

A pointer to a tree (the root directory at that moment)

Pointers to parent commits (the history leading to this point)

Author information (who wrote the changes)

Committer information (who applied the changes)

Timestamps

A commit message explaining the changes

Commit: abc123def456...

tree: def456...

parent: 789012...

author: John <john@example.com> 1699900000 +0000

committer: John <john@example.com> 1699900000 +0000

Add login featureWhen you run git commit, Git creates a new commit object. This commit points to a tree representing your project’s current state. The parent pointer links back to the previous commit, forming a chain. This chain is your project’s history.

The parent pointer is what makes Git a version control system rather than just a filesystem. By following parent pointers backward, Git can reconstruct any previous state of your project.

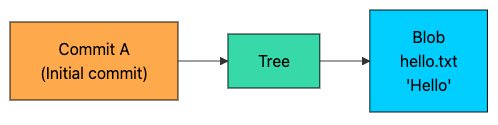

The following diagram shows how a complete snapshot looks in Git’s object model:

With blobs, trees, and commits, Git has everything it needs to store and track your project. But where do these objects actually live?

3. How Git Stores Objects

When you run git init, Git creates the .git directory with this structure:

.git/

├── HEAD (contains: ref: refs/heads/main)

├── config (repository configuration)

├── description (used by GitWeb, rarely relevant)

├── hooks/ (scripts triggered by Git events)

├── info/ (exclude patterns, other info)

├── objects/ (the object database, initially empty)

│ ├── info/

│ └── pack/

└── refs/ (references to commits)

├── heads/ (branch pointers, initially empty)

└── tags/ (tag pointers)All Git objects live inside your repository’s .git/objects directory.

Git uses a simple organization scheme: the first two characters of an object’s hash become a subdirectory name, and the remaining 38 characters become the filename.

.git/objects/

├── 5d/

│ └── d01c177f5d7d1be5346a5bc18a569a7410c2ef (blob)

├── 4c/

│ └── 5f8a2b9d3e7f1a6b0c8d5e2f9a4b7c3d6e0f1a (tree)

├── a1/

│ └── b2c3d4e5f6g7h8i9j0k1l2m3n4o5p6q7r8s9t0 (commit)

└── ...This two-character prefix prevents any single directory from containing too many files, which could slow down filesystem operations.

Before writing an object to disk, Git also compresses it with zlib. A 1MB source file might shrink to ~100KB or less. Combine that with content-addressable deduplication (identical content stored once), and Git repositories stay surprisingly small even with long histories.

Inspecting Objects Directly

Git provides low-level commands to examine objects. These “plumbing” commands reveal what is happening under the hood:

# Determine an object's type (blob, tree, commit, or tag)

git cat-file -t 5dd01c17

# Display an object's contents

git cat-file -p 5dd01c17

# Examine what a commit contains

git cat-file -p HEADTry running git cat-file -p HEAD in a repository. You will see the tree pointer, parent pointer, author information, and commit message. Then run git cat-file -p on that tree hash to see the directory listing.

Objects explain how Git stores data, but they do not yet explain the day-to-day workflow. When you edit a file, stage it, and commit, you move data through three distinct areas.

Let’s look at those next.

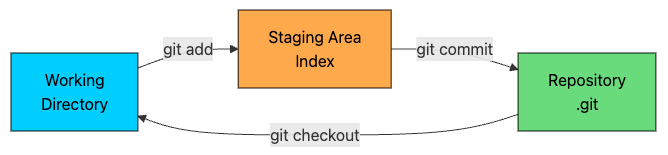

4. The Three Areas

Git organizes your work into three separate areas. Understanding these areas is the key to understanding why Git commands behave the way they do.

Working Directory: Your Workspace

The working directory is what you see in your file explorer. These are actual files on your filesystem that you open in your editor, modify, and save.

The working directory is not Git. It is simply a checkout of one particular version of your project. Git can delete it and recreate it from any commit in seconds.

This is why you can switch branches instantly, even in large projects. Git is not moving files around; it is regenerating the working directory from its object database.

Staging Area: Your Draft

The staging area (also called the index) lives in a single file at .git/index. It represents the exact snapshot of what your next commit will contain.

When you run git add README.md, Git does two things:

Creates a blob object from the file’s current contents (or reuses an existing blob if the contents match)

Updates the index to associate the filename with that blob’s hash

Think of the staging area as a draft of your next commit. You can add files to it incrementally, remove files from it, and review exactly what is staged before committing.

This gives you precise control over what goes into each commit.

# See what is staged versus what is modified

git status

# See the actual diff of staged changes

git diff --staged

# Remove a file from staging (keep the working directory change)

git restore --staged README.mdWhy have a staging area at all?

Imagine you changed five files. Three are part of a bug fix, and two are unrelated cleanup.

Without staging, you either commit everything together or do awkward manual juggling. With staging, you commit the bug fix first, then commit the cleanup separately. Your history stays clean and easy to follow.

Repository: The Source of Truth

The repository is the .git directory. It contains everything: the object database (all blobs, trees, commits), references (branches, tags), configuration, hooks, and more.

When you run git commit, Git:

Creates a tree object from the current index

Creates a commit object pointing to that tree, with the current HEAD as parent

Updates the current branch to point to this new commit

The repository is the source of truth for your project. The working directory and staging area are just convenient views into it. If you delete your working directory but keep .git, you can restore everything. If you delete .git, your history is gone.

Now that we understand where data lives, let’s understand what actually happens when you commit files.

5. How Commits Work

A Git commit is not a “bundle of changes.” It is a snapshot of your project at a moment in time, plus a pointer to its parent commit(s).

Let’s trace what Git creates as you commit.

Creating Your First Commit

echo "Hello" > hello.txt

git add hello.txt

git commit -m "Initial commit"At this point, Git writes three objects:

Blob: the contents of

hello.txt("Hello\n")Tree: a directory listing that maps

hello.txtto that blob (and stores file mode like100644)Commit: points to the tree and stores metadata (author, timestamp, message)

The commit does not contain file contents directly. It contains a pointer to the root tree, and the tree points to blobs.

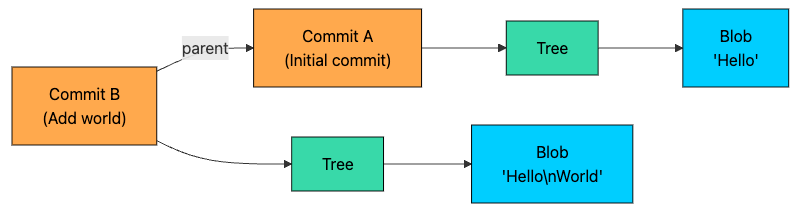

Creating a Second Commit

Now change the file and commit again:

echo "World" >> hello.txt

git commit -am "Add world"What changes inside Git?

hello.txthas new content, so Git creates a new blob for the new contents.Because the file now points to a different blob, Git creates a new tree.

Git creates a new commit pointing to that new tree, and sets its parent to the previous commit.

Notice what did not happen:

Git did not modify Blob A.

Git did not overwrite Tree A.

Git did not “update” Commit A.

Git objects are effectively immutable. New state means new objects, while unchanged objects are reused.

Also notice the storage efficiency: even though commits are “snapshots,” Git is not duplicating everything each time. Only objects that changed are new. Everything else is referenced again.

Snapshots, Not Diffs

A common misconception is that Git stores diffs between commits, like:

Commit 1 + Diff -> Commit 2 + Diff -> Commit 3 ...That is not how Git works.

Git stores snapshots:

Each commit points to a tree

That tree represents the full directory state at that moment

Git computes diffs only when you ask for them (for example

git diff,git show, PR views)

So the internal model is closer to this:

Snapshot (Tree) A -> Commit A

Snapshot (Tree) B -> Commit B

Snapshot (Tree) C -> Commit CThis is why operations like checkout are fast. Git does not replay every change from the beginning of time. It simply reads the tree for the commit you want and regenerates the working directory from that snapshot.

6. How Branches Work

Here is the fact that changes how you think about Git: a branch is just a pointer to a commit.

That is the entire implementation. A branch is a small file containing a 40-character commit hash. The file for your main branch lives at .git/refs/heads/main.

.git/refs/heads/main: a1b2c3d4e5f6g7h8i9j0k1l2m3n4o5p6q7r8s9t0

.git/refs/heads/feature: x9y8z7w6v5u4t3s2r1q0p9o8n7m6l5k4j3i2h1g0Creating a branch is nearly instantaneous because Git only creates a tiny file. There is no copying of files, no duplicating history. Just a 41-byte file (40 characters plus a newline) pointing to an existing commit.

HEAD: Tracking Your Current Position

HEAD is a special reference that tells Git where you are. In most cases, HEAD points to a branch name rather than directly to a commit:

.git/HEAD: ref: refs/heads/mainThis means: “you are on main.” Git resolves your current commit by following pointers: HEAD → main → commit → tree → files

When you create a new branch using git branch feature, Git creates .git/refs/heads/feature containing the current commit hash. No new commits, no copying.

When you switch branches with git checkout feature, Git updates HEAD to point to refs/heads/feature, then regenerates your working directory and index to match that branch’s commit.

Sometimes HEAD points directly to a commit hash instead of a branch name. This is called detached HEAD state. It happens when you checkout a specific commit by its hash or checkout a tag.

In this state, any new commits you create are not attached to a branch and can become “lost” if you switch away without creating a branch to preserve them.

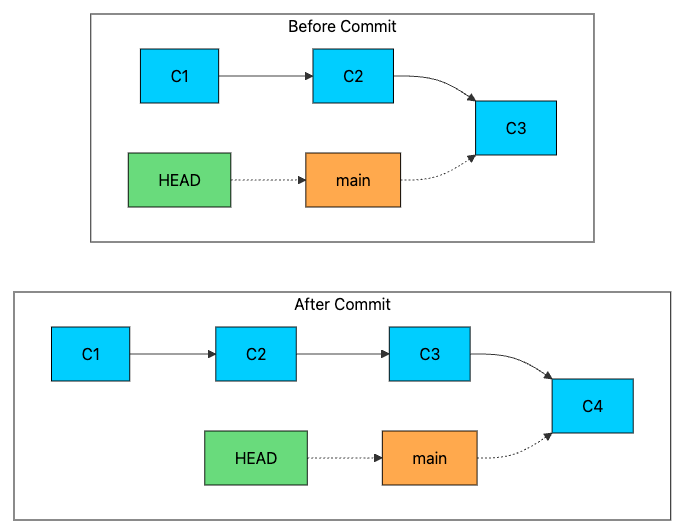

How Commits Advance Branches

When you create a new commit while on a branch, Git advances that branch pointer.

The new commit (C4) has C3 as its parent. Then Git updates .git/refs/heads/main to contain C4’s hash. HEAD still points to main, but main now points to the new commit.

This pointer-based design explains why Git branching is so fast and cheap. There is no copying involved. Creating ten branches from the same commit means creating ten 41-byte files, all pointing to the same commit hash.

But branches diverge. Different developers make different changes on different branches. Eventually, those branches need to come back together. Let’s see how merging works.

7. How Merging Works

Merging combines the work from two branches into one. Git handles merging differently depending on how the branches have diverged.

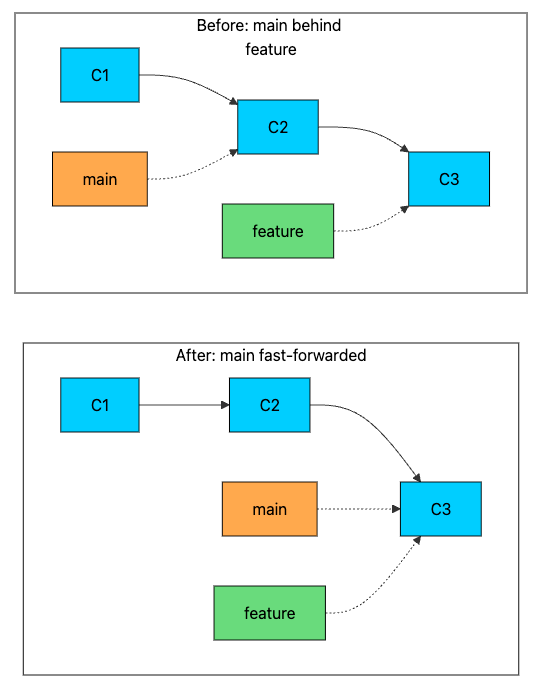

Fast-Forward Merge: The Simple Case

The simplest merge happens when the target branch has not moved since the source branch was created. In this case, Git performs a fast-forward merge: it simply moves the target branch pointer forward to match the source branch.

No new commit is created. Git just updates the main branch pointer from C2 to C3. Fast-forward merges are instant and create a linear history.

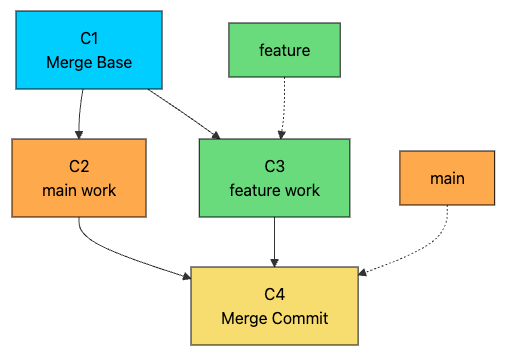

Three-Way Merge: When Branches Diverge

When both branches have new commits since they diverged, Git performs a three-way merge. It needs three pieces of information:

The merge base: the common ancestor where the branches diverged

The current branch tip: where your branch is now (ours)

The other branch tip: what you are merging in (theirs)

Git compares both branch tips against the merge base to determine what changed on each side. Changes that only appear on one side are applied automatically. Changes that conflict (both sides modified the same lines) require manual resolution.

The resulting merge commit (C4) has two parents: C2 from main and C3 from feature. This preserves the complete history of both branches. You can trace back through either parent to see exactly what work happened on each branch.

Handling Conflicts

When Git cannot automatically merge (the same lines were changed differently on both sides), it marks the conflicts in your files:

<<<<<<< HEAD

const timeout = 5000;

=======

const timeout = 10000;

>>>>>>> featureEverything between <<<<<<< HEAD and ======= is from your current branch. Everything between ======= and >>>>>>> feature is from the branch being merged.

You resolve the conflict by editing the file to contain what you actually want, removing the conflict markers, then staging and committing.

Merging preserves the complete history of both branches, but it creates merge commits that can clutter the history. There is another way to integrate changes that results in a cleaner, linear history.

8. How Rebase Works

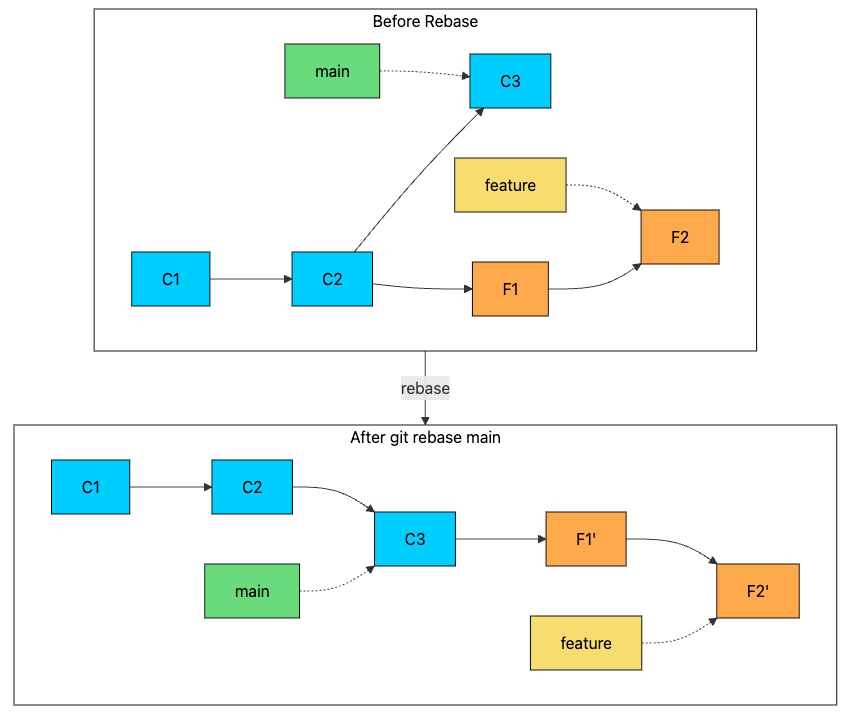

Rebasing is an alternative to merging that rewrites history to create a linear sequence of commits.

Instead of creating a merge commit that ties two branches together, rebase moves your commits to appear as if they were created on top of the target branch.

When you run git rebase main while on a feature branch, Git:

Finds the common ancestor of both branches

Saves the commits that are unique to your feature branch

Resets your branch to the tip of main

Replays your saved commits one by one on top

Notice that F1 and F2 become F1' and F2' after rebasing. The prime marks indicate these are new commits with different hashes. Even though the changes are identical, the commits have different parent pointers, which means different SHA-1 hashes.

The original commits still exist in the object database (and are recoverable via reflog) but are no longer reachable from any branch.

9. How Git Optimizes Storage

So far, we have discussed “loose objects”: individual files in .git/objects/ named by their hash. This is simple and fast for writing new objects, but it does not scale perfectly.

Two issues show up as a repo grows:

Filesystem overhead: thousands (or millions) of tiny files can slow down filesystems.

Wasted space across versions: even though Git stores snapshots, many snapshots differ only slightly.

Git solves both problems with pack files.

Pack Files

Instead of keeping every object as a separate file, Git periodically (during git gc, push, fetch, or clone) bundles many objects together into a pack:

.git/objects/pack/

├── pack-abc123def456.idx (index for fast lookup)

└── pack-abc123def456.pack (compressed objects with deltas)The

.packfile holds the actual compressed, delta-encoded data.The

.idxfile is an index that lets Git locate any object inside the pack quickly.

This reduces file count dramatically and makes large repositories more efficient to store and transfer.

How packing saves space

When Git creates a pack, it applies three main optimizations:

Grouping: Git clusters related objects (for example, multiple versions of the same file) so it can compress them effectively.

Delta compression: Instead of storing every version in full, Git stores one full version and then stores deltas (differences) for the others. Older versions can be reconstructed by applying deltas.

Compression: The packed data is compressed (zlib), just like loose objects, but now Git can often compress even better because it is working with a larger, more structured dataset.

The Impact on Repository Size

Imagine a 1MB configuration file modified 100 times.

Without packing, Git would store many full versions (each compressed, but still substantial). You might end up with something on the order of tens of megabytes or more across history.

With packing, Git can store one full version plus small deltas for the other 99 versions. If each change touches only a few lines, each delta could be only a few kilobytes, so the total might be closer to a couple of megabytes.

This is why repositories with years of history and thousands of commits can still clone in a reasonable size. Git is not shipping every full file version. It is shipping a compact representation built from packed objects and deltas.

When Packing Happens

You usually do not need to trigger packing manually. Git does it for you:

git gcexplicitly runs garbage collection and repackinggit push/git fetch/git cloneoften involve packing or repacking for efficient transferGit can also run GC automatically when loose objects grow past certain thresholds

You rarely think about pack files day to day, but they are a big reason Git scales so well and why repository sizes are manageable despite storing complete history.

Key Takeaways

Git is a content-addressable filesystem. Every piece of data is stored by its SHA-1 hash. Same content, same hash, stored once.

Three object types matter. Blobs store file contents. Trees store directory structure. Commits store snapshots with history links.

The three areas structure your workflow. Working directory for editing, staging area for drafting commits, repository for permanent storage.

Branches are just pointers. A branch is a 41-byte file containing a commit hash. Creating branches is instant. Switching branches regenerates the working directory.

Merging connects histories. Fast-forward when possible, three-way merge when branches diverge. Conflicts happen when the same lines change differently.

Pack files keep Git efficient. Delta compression and grouping allow Git to store extensive history in surprisingly little space.

Thank you for reading!

If you found it valuable, hit a like ❤️ and consider subscribing for more such content every week.

If you have any questions/suggestions, feel free to leave a comment.

That was a good depth into how Git operates. Perfect for those who are curious to know about the BTS of tech. Good one Ashish.

Nice bro