Polling vs. Long Polling vs. SSE vs. WebSockets vs. Webhooks

Whether you are chatting with a friend or playing an online game, updates show up in real time without hitting “refresh”.

Behind these seamless experiences lies a key engineering decision: how does the server notify the client (or another system) when new data is available?

The traditional HTTP was built around a simple request-response flow: the client asks, the server answers. But in real-time systems, the server often needs to push updates proactively, sometimes continuously.

That’s where communication models like Long Polling, Server-Sent Events (SSE), WebSockets, and Webhooks come in.

In this article, we’ll break down how each one works, it’s pros and cons, where it fits best, and how to choose the right approach for a production system or a system design interview.

Let's start with the most straightforward approach.

1. Polling

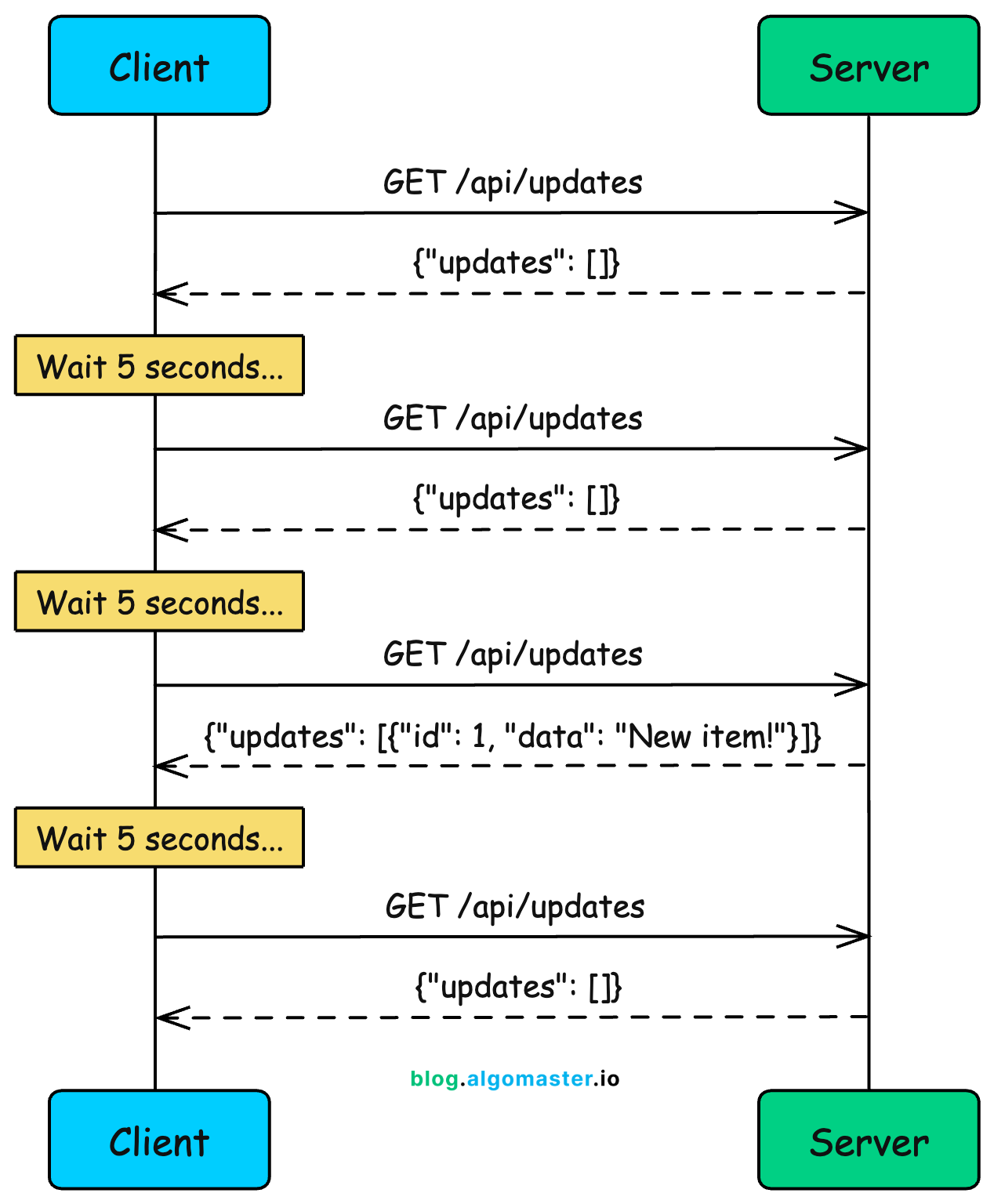

Polling is the simplest approach to getting updates from a server. The client sends requests to the server at regular intervals, checking if anything has changed.

Think of it like refreshing your email inbox every few minutes to check for new messages.

How It Works

Client sends an HTTP request to the server

Server responds immediately with current data (or empty response)

Client waits for a fixed interval (e.g., 5 seconds)

Client sends another request

Repeat indefinitely

Notice something wasteful here? The client keeps asking even when nothing has changed. Three out of four requests in this diagram returned empty responses.

In real applications, this ratio is often much worse. You might make 100 requests before getting a single meaningful update.

Example: Weather Dashboard

Imagine you’re building a weather dashboard. Weather data doesn’t change that frequently, maybe every 15-30 minutes at most.

Polling makes sense here:

setInterval(async () => {

const response = await fetch('/api/weather?city=london');

const weather = await response.json();

updateDashboard(weather);

}, 60000); // Poll every minuteEvery minute, your client asks for the current weather. The server responds with temperature, humidity, conditions, and so on.

Pros

Simple to implement: Just a regular HTTP request in a loop. No special protocols or libraries needed.

Works everywhere: Any HTTP client can do polling. No firewall or proxy issues.

Stateless: Each request is independent. The server doesn’t need to maintain any connection state.

Easy to debug: Standard HTTP requests that show up in network logs and dev tools.

Cons

Wasted requests: Most requests return empty responses when nothing has changed. This wastes bandwidth and server resources.

High latency: Updates are delayed by the polling interval. If you poll every 10 seconds, updates can take up to 10 seconds to reach the client.

Doesn’t scale: 10,000 clients polling every second means 10,000 requests per second, even when nothing is happening.

Trade-off between latency and efficiency: Shorter intervals mean faster updates but more wasted requests. Longer intervals mean fewer requests but slower updates.

When to Use

Low-frequency updates: Weather data, daily reports, or anything that changes infrequently

Simple systems: MVPs, internal tools, or situations where simplicity matters more than efficiency

Legacy compatibility: When you need to support older clients or environments that can’t use modern techniques

Acceptable latency: When delays of several seconds (or minutes) are acceptable

Polling is a reasonable starting point, but you’ll quickly feel its limitations as your application grows. If you need faster updates without drowning your server in requests, that’s where long polling comes in.

2. Long Polling

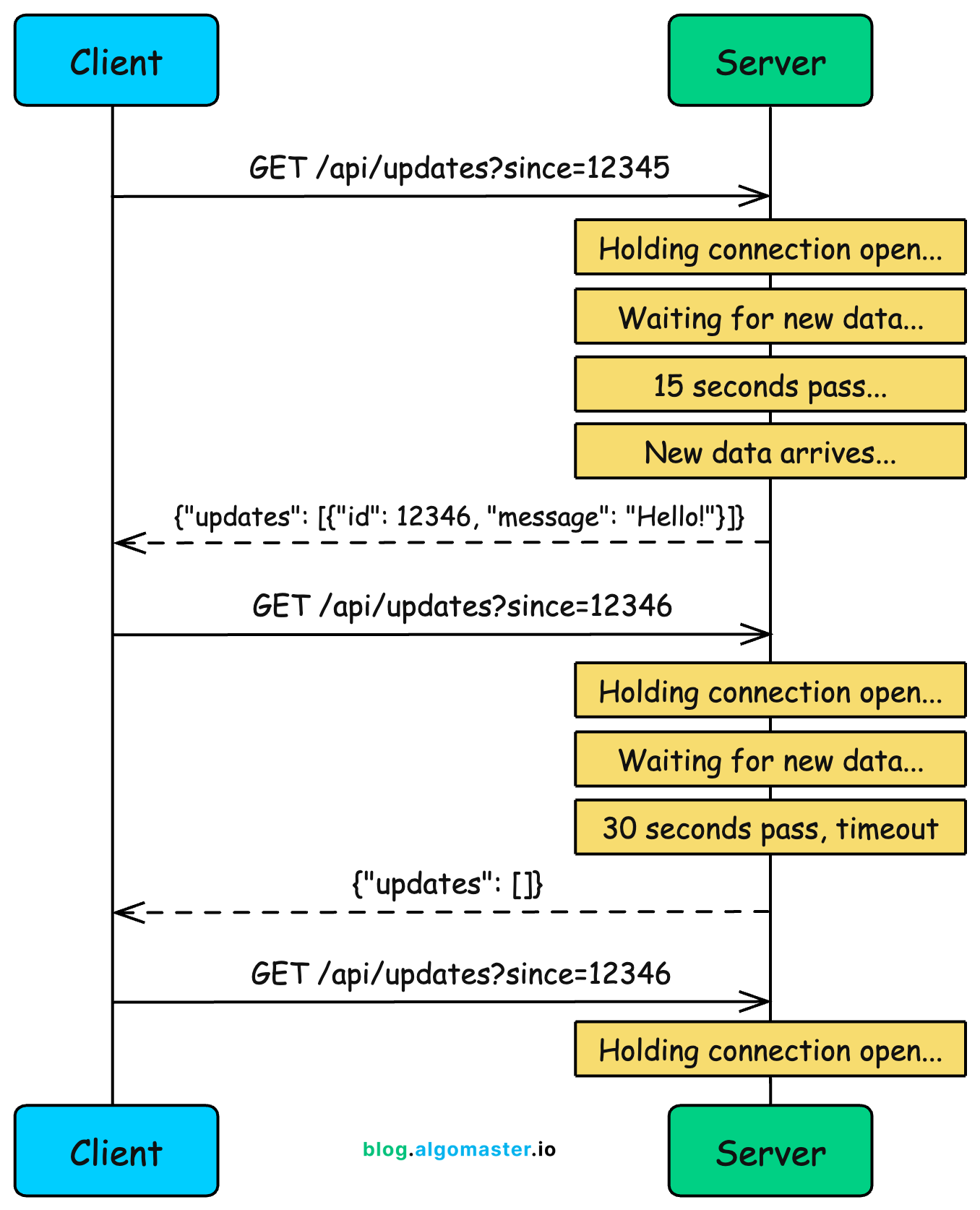

Long polling improves on regular polling by having the server hold the request open until new data is available (or a timeout occurs). Instead of the client repeatedly asking “anything new?”, the server waits and responds only when there’s something to report.

This was the technique that powered early real-time applications like Facebook Messenger before WebSockets became widely supported.

How It Works

Client sends an HTTP request to the server

Server holds the connection open (doesn’t respond immediately)

When new data arrives, server sends the response

Client immediately sends another request

If no data arrives within the timeout period, server sends an empty response and client reconnects

The key insight is that the server only responds when it has something meaningful to say. This eliminates the wasted “nothing new” responses of regular polling.

Example: Chat Application

Consider a chat app built with long polling. When you open a conversation, your browser sends a request like:

GET /api/messages?conversation=123&after=msg_999The server checks if there are any messages newer than msg_999. If not, instead of returning an empty response, it holds the connection and waits.

When someone sends a new message to that conversation, the server immediately responds with the new message. Your client receives it, renders it in the chat window, and immediately opens a new connection to wait for the next message.

There’s an important detail here: the timeout. HTTP connections can’t stay open forever. Proxies, load balancers, and browsers all have limits. So the server needs to respond eventually, even if nothing happened.

A typical timeout is 30 seconds. If 30 seconds pass with no new data, the server sends an empty response, the client immediately reconnects, and the wait continues.

Pros

Near real-time: Updates arrive almost instantly when they happen, without waiting for a polling interval.

Fewer wasted requests: Responses almost always contain useful data, not empty “nothing new” responses.

Works through proxies and firewalls: Uses standard HTTP, so it works in restrictive network environments where WebSockets might be blocked.

Simpler than WebSockets: No protocol upgrade, no special handling for connection state.

Cons

Resource intensive: Each waiting client holds a connection open on the server. With 10,000 clients, you need 10,000 open connections.

Timeout handling complexity: You need to handle timeouts, reconnection logic, and edge cases like the client receiving data just as the timeout expires.

Head-of-line blocking: If multiple events happen quickly, they may get batched together or delivered out of order.

HTTP overhead: Every response requires a new request, and each request carries HTTP headers. This overhead adds up.

When to Use

Chat applications (historically): Before WebSocket support was universal, long polling powered most chat systems

Fallback mechanism: When WebSockets aren’t available due to proxy or firewall restrictions

Server-initiated updates: When clients mostly receive data rather than send it

Moderate scale: Works well for hundreds or thousands of concurrent connections, but gets expensive at massive scale

Long polling feels like “almost real-time,” but it’s still request-response at heart. The client still initiates every exchange. What if the server could just push data to clients whenever it wants? That’s exactly what Server-Sent Events enable.

3. Server-Sent Events (SSE)

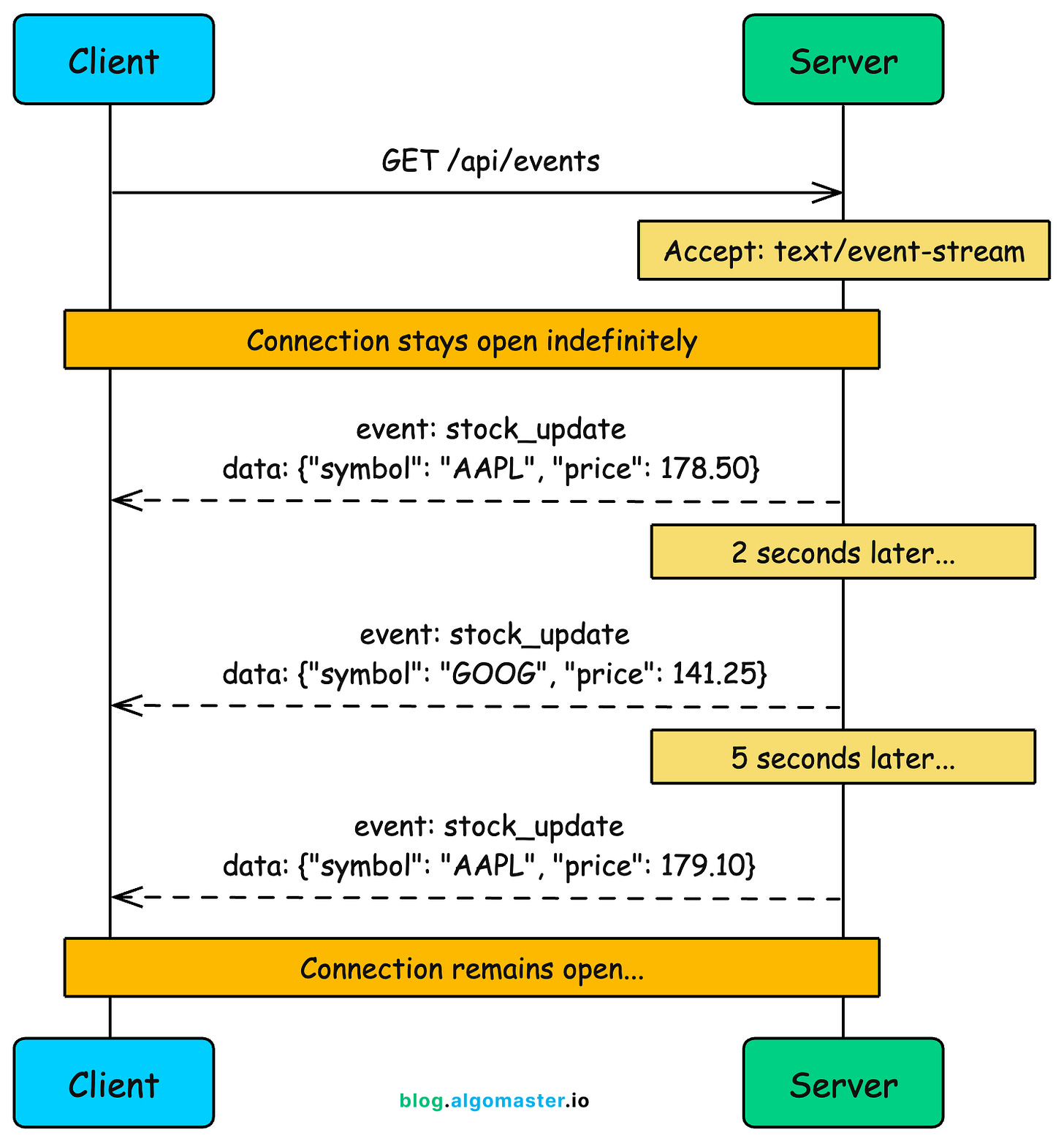

Server-Sent Events (SSE) is a standard that allows a server to push updates to a client over a single, long-lived HTTP connection. Unlike polling where the client keeps asking, SSE opens a connection once and the server sends data whenever it has something to share.

Think of it like subscribing to a news feed. You sign up once, and updates stream to you automatically.

How It Works

Client opens a connection using the

EventSourceAPIServer keeps the connection open and sends events as they occur

Events are sent as plain text in a specific format

If the connection drops, the browser automatically reconnects

Server can send different event types for clients to handle differently

The data flows in one direction: from server to client. If the client needs to send data back, it uses separate HTTP requests.

Example: Stock Price Dashboard

const eventSource = new EventSource('/api/stock-prices');

eventSource.addEventListener('price_update', (event) => {

const data = JSON.parse(event.data);

updatePriceDisplay(data.symbol, data.price);

});

eventSource.addEventListener('alert', (event) => {

showNotification(JSON.parse(event.data).message);

});The server streams price updates as they happen. The client handles different event types (price updates vs alerts) with separate listeners.

The SSE Event Format

SSE uses a simple text-based format that’s easy to read and debug:

event: price_update

data: {"symbol": "AAPL", "price": 150.25}

id: 12345

event: price_update

data: {"symbol": "GOOG", "price": 2840.50}

id: 12346The id field enables resumption. If the connection drops, the browser sends Last-Event-ID in the reconnection request, and the server can replay missed events.

Pros

Simple API: The browser’s

EventSourceAPI handles connections, reconnection, and parsing automatically.Automatic reconnection: If the connection drops, the browser reconnects automatically with the last event ID.

HTTP/2 multiplexing: Multiple SSE streams can share a single TCP connection, reducing overhead.

Lower overhead than polling: One connection, no repeated request headers, no wasted “nothing new” responses.

Text-based and debuggable: Events are plain text, easy to inspect in browser dev tools.

Cons

Unidirectional only: Data flows server to client only. The client can’t send data over the same connection.

Connection limits: Browsers limit connections per domain (typically 6 for HTTP/1.1). This matters if you need multiple SSE streams.

No binary data: SSE is text-only. Binary data must be base64 encoded, which adds overhead.

Less flexible than WebSockets: No custom subprotocols or extensions.

When to Use

Live feeds: News feeds, social media timelines, activity streams

Real-time dashboards: Stock tickers, analytics dashboards, monitoring systems

Notifications: Push notifications, alerts, status updates

Any scenario where data flows one way: From server to client, with no client-to-server messages needed

SSE works great when you only need server-to-client communication. But many applications need bidirectional communication, where both sides send and receive messages freely. That’s where WebSockets shine.

4. WebSockets

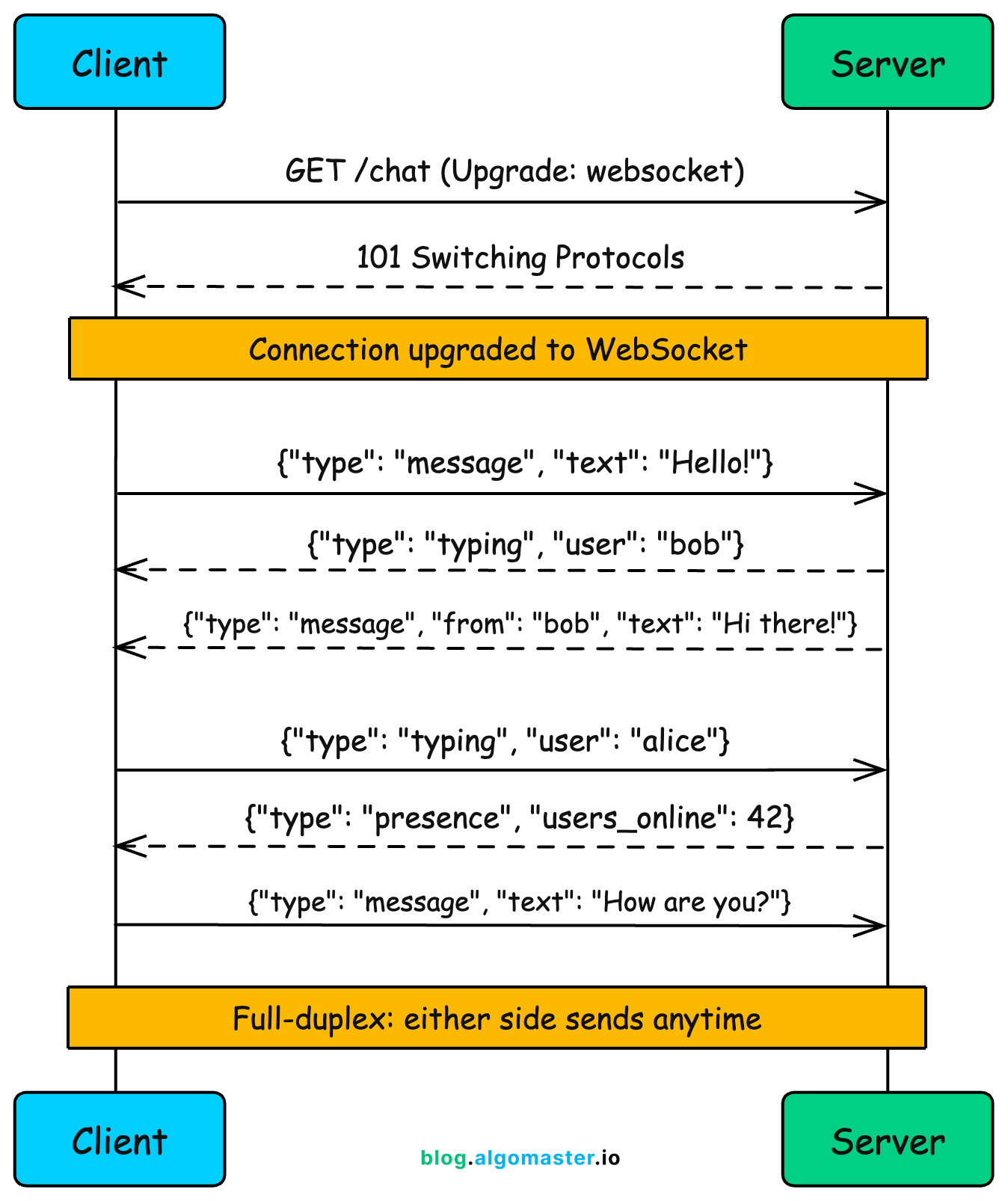

WebSockets represent a fundamental departure from HTTP’s request-response model. Instead of one side asking and the other answering, WebSockets establish a persistent, bidirectional channel where either party can send messages at any time.

This is the technology behind real-time chat apps like Slack and Discord, multiplayer games, and collaborative tools like Google Docs.

How It Works

A WebSocket connection starts as HTTP, then “upgrades” to a different protocol:

Client initiates a WebSocket handshake via HTTP upgrade request

Server accepts and upgrades the connection from HTTP to WebSocket

Both sides can now send messages freely

Connection stays open until either side closes it

The Upgrade Handshake

The initial HTTP handshake looks like this:

GET /chat HTTP/1.1

Host: server.example.com

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-WebSocket-Key: dGhlIHNhbXBsZSBub25jZQ==

Sec-WebSocket-Version: 13

Origin: https://example.comThe server responds:

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-WebSocket-Accept: s3pPLMBiTxaQ9kYGzzhZRbK+xOo=Once upgraded, the connection is no longer HTTP. It’s now a WebSocket connection, a binary framing protocol optimized for low-overhead messaging.

Example: Chat Application

Here’s how a chat client might work:

const socket = new WebSocket('wss://chat.example.com/room/123');

socket.onopen = () => {

socket.send(JSON.stringify({

type: 'join',

username: 'alice'

}));

};

socket.onmessage = (event) => {

const data = JSON.parse(event.data);

if (data.type === 'message') {

displayMessage(data.user, data.text);

} else if (data.type === 'typing') {

showTypingIndicator(data.user);

}

};

// Send a message

function sendMessage(text) {

socket.send(JSON.stringify({

type: 'message',

text: text

}));

}Both client and server can send messages at any time. The server can broadcast typing indicators while the client sends messages, all over the same connection.

Pros

True real-time: Messages arrive with minimal latency. No polling, no waiting.

Bidirectional: Both sides can send messages independently, without waiting for a response.

Low overhead: After the initial handshake, message framing is minimal (as little as 2 bytes per frame).

Binary support: WebSockets can send binary data directly, unlike SSE.

Subprotocols: You can negotiate application-level protocols (like STOMP or MQTT) over WebSocket.

Cons

Stateful connections: The server must maintain state for each connection. This complicates horizontal scaling since you need sticky sessions or a pub/sub layer.

Connection management: You need to handle disconnections, reconnections, heartbeats, and timeouts manually.

Proxy and firewall issues: Some corporate proxies don’t handle WebSocket upgrades properly, blocking connections.

More complex than HTTP: Debugging is harder. Messages don’t show up in standard HTTP logs. You need WebSocket-aware tools.

Resource intensive: Each connection consumes server memory and file descriptors. At massive scale, this adds up.

When to Use

Chat applications: Slack, Discord, WhatsApp Web

Multiplayer games: Real-time game state synchronization

Collaborative editing: Google Docs, Figma, Notion

Trading platforms: Where milliseconds matter

Live interactions: Auctions, live streaming with chat

The rule of thumb: if you truly need bidirectional real-time communication, WebSockets are probably your answer. But if data only flows one way (server to client), SSE is simpler. And if you’re building server-to-server integrations, there’s yet another approach.

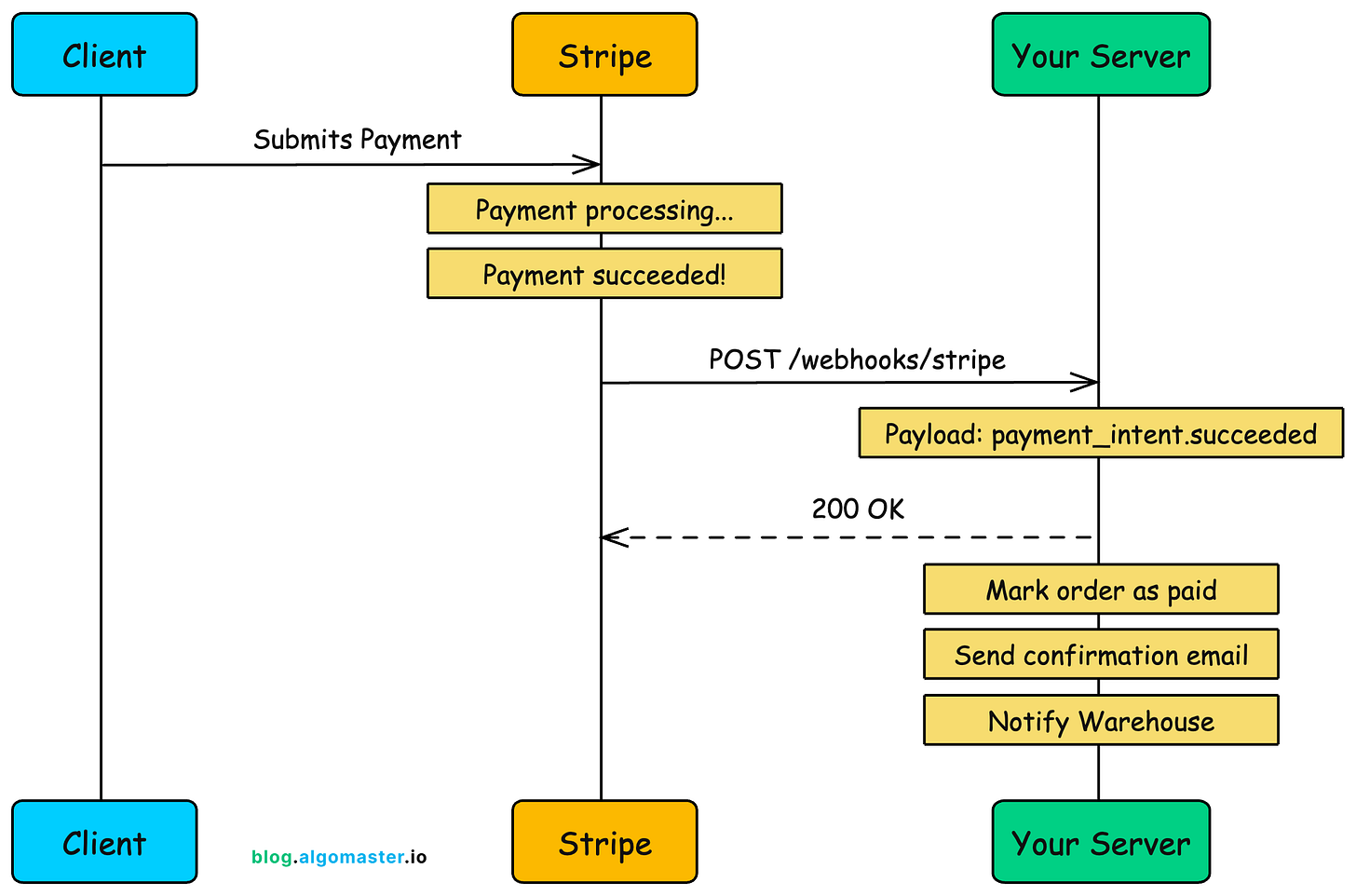

5. Webhooks

Everything we’ve discussed so far involves browsers or mobile apps talking to servers.

Webhooks flip the script entirely: they’re how servers talk to other servers. Instead of clients pulling data from servers, webhooks let one server push data to another when events occur.

Think of webhooks as “reverse APIs.” Instead of you calling an API to get data, the API calls you when something happens.

How It Works

You register a callback URL with the provider (e.g., Stripe, GitHub)

You specify which events you want to receive

When those events occur, the provider sends an HTTP POST to your URL

Your server processes the event and responds with 200 OK

If delivery fails, the provider typically retries with exponential backoff

Example: Stripe Payment Webhooks

When integrating Stripe, you configure a webhook endpoint in their dashboard:

https://api.yourapp.com/webhooks/stripeAnd you subscribe to events like payment_intent.succeeded, customer.subscription.created, or invoice.payment_failed.

When a customer’s payment succeeds, Stripe sends you something like:

{

"id": "evt_1PoJkD2eZvKYlo2CmOJbvwD9",

"type": "payment_intent.succeeded",

"created": 1713681701,

"data": {

"object": {

"id": "pi_3JhdNe2eZvKYlo2C1IqojYg9",

"amount": 4999,

"currency": "usd",

"customer": "cus_xyz789",

"metadata": {

"order_id": "order_12345"

}

}

}

}Your server receives this, verifies the signature (to ensure it really came from Stripe), and then does whatever needs doing: update the order status, send a receipt, decrement inventory, notify fulfillment.

Security Considerations

Webhooks create a publicly accessible endpoint that anyone could try to call. You must verify that requests actually come from the expected source.

Most providers include a signature in the headers:

Stripe-Signature: t=1617000000,v1=abc123def456...You verify this by computing an HMAC of the request body using your webhook secret:

expected = hmac.new(secret, payload, hashlib.sha256).hexdigest()

if not hmac.compare_digest(expected, signature):

return 403 # Reject the requestPros

Instant notifications: Events arrive immediately when they happen, no polling delay.

No wasted requests: You only receive HTTP calls when something actually happens.

Decoupled systems: The provider doesn’t need to know your internal architecture. It just calls your URL.

Scales well: No persistent connections to maintain. Each event is a single HTTP request.

Standard HTTP: Easy to debug, log, and monitor with standard tools.

Cons

Requires public endpoint: Your server must be accessible from the internet. Local development requires tools like ngrok.

Delivery isn’t guaranteed: If your server is down, you miss events. You need idempotent handlers and event replay mechanisms.

Retry handling: Providers retry failed deliveries, so your handler must be idempotent (processing the same event twice should be safe).

Security surface: A public endpoint increases attack surface. Signature verification is essential.

No backpressure: If events arrive faster than you can process them, you need queuing and rate limiting.

When to Use

Payment processing: Stripe, PayPal, Square notifications

CI/CD pipelines: GitHub push events triggering builds

Third-party integrations: Any external service that needs to notify your system

Microservices communication: Event-driven architectures between internal services

Audit and compliance: Receiving notifications about account changes, security events

The pattern is clear: when one server needs to notify another about events, webhooks are almost always the right approach. They’re not for browser clients (which can’t expose public endpoints), but for backend-to-backend communication, they’re the gold standard.

7. Choosing the Right Approach

With five options, how do you pick the right one? Consider these four factors:

Question 1: Who Needs to Talk to Whom?

This is the most fundamental question.

Server notifying another server? Webhooks. There’s rarely a good reason to use anything else for backend-to-backend event notification.

Server pushing updates to clients (one-way)? SSE is usually the best choice. It’s simpler than WebSockets and handles reconnection automatically.

Truly bidirectional client-server communication? WebSockets. If both sides need to send messages freely, nothing else really works.

Question 2: How Fast Do Updates Need to Arrive?

Minutes or hours are acceptable? Polling is fine. Don’t over-engineer.

Seconds are acceptable? Long polling or SSE both work well.

Milliseconds matter? WebSockets. There’s nothing faster for browser-to-server communication.

Question 3: What Infrastructure Constraints Exist?

Corporate firewalls blocking WebSockets? Fall back to long polling or SSE.

Need to support old browsers or restricted environments? Polling is the safest choice.

Horizontal scaling is critical? SSE or webhooks scale more easily than WebSockets.

Running serverless or can’t maintain persistent connections? Webhooks for server-to-server. Polling for client-to-server.

Question 4: What’s the Acceptable Complexity Budget?

Every approach has a complexity cost.

Polling: Almost zero complexity. Anyone can implement it.

SSE: Low client complexity (browser handles it), moderate server complexity.

Long Polling: Moderate complexity on both sides. Edge cases are tricky.

WebSockets: High complexity. Connection management, scaling, state synchronization.

Webhooks: Moderate complexity. Security verification, idempotency, error handling.

Match the tool to the actual requirements.

Thank you for reading!

If you found it valuable, hit a like ❤️ and consider subscribing for more such content every week.

If you have any questions/suggestions, feel free to leave a comment.

Really informative! Love the way you explained the pros and cons of each approach along with their use cases.

Need more content like this!