How to Scale a System from 0 to 10 million+ Users

Scaling is a complex topic, but after working at big tech on services handling millions of requests and scaling my own startup (AlgoMaster.io) from scratch, I’ve realized that most systems evolve through a surprisingly similar set of stages as they grow.

The key insight is that you should not over-engineer from the start. Start simple, identify bottlenecks, and scale incrementally.

In this article, I’ll walk you through 7 stages of scaling a system from zero to 10 million users and beyond. Each stage addresses the specific bottlenecks that show up at different growth points. You’ll learn what to add, when to add it, why it helps, and the trade-offs involved.

Whether you’re building an app or website, preparing for system design interviews, or just curious about how large-scale systems work, understanding this progression will sharpen they way you think about architecture.

Disclaimer: The user ranges and numbers mentioned in this article are approximate and intended to illustrate a scaling journey. Actual thresholds will vary depending on your product, workload characteristics, and traffic patterns.

Stage 1: Single Server (0-100 Users)

When you’re just starting out, your first priority is simple: ship something and validate your idea. Optimizing too early at this stage wastes time and money on problems you may never face.

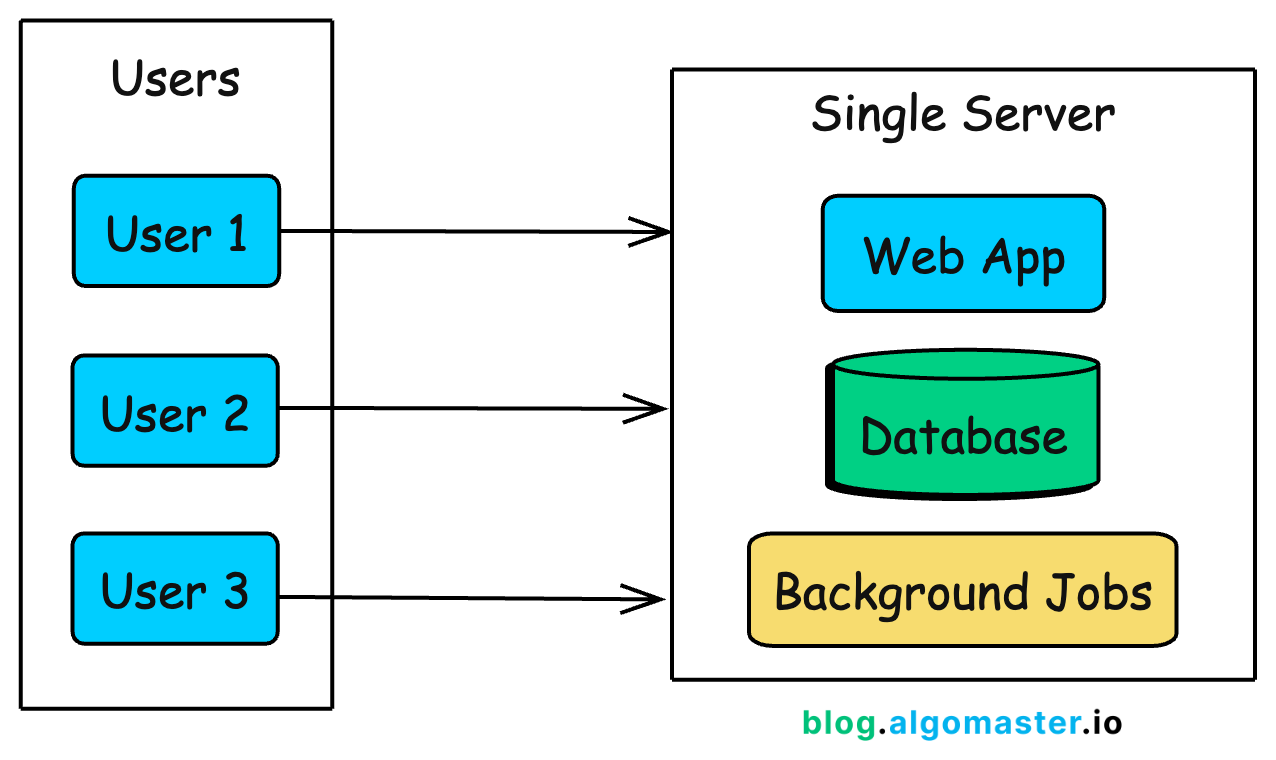

The simplest architecture puts everything on a single server: your web application, database, and any background jobs all running on the same machine.

This is how Instagram started. When Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger launched the first version in 2010, 25,000 people signed up on day one.

They didn’t over-engineer upfront. With a small team and a simple setup, they scaled in response to real demand, adding capacity as usage grew, rather than building for hypothetical future traffic.

What This Architecture Looks Like

In practice, a single-server setup means:

A web framework (Django, Rails, Express, Spring Boot) handling HTTP requests

A database (PostgreSQL, MySQL) storing your data

Background job processing (Sidekiq, Celery) for async tasks

Maybe a reverse proxy (Nginx) in front for SSL termination

All of these run on one virtual machine. Your cloud provider bill might be $20-50/month for a basic VPS (DigitalOcean Droplet, AWS Lightsail, Linode).

Why This Works for Early Stage

At this stage, simplicity is your biggest advantage:

Fast deployment: One server means one place to deploy, monitor, and debug.

Low cost: A single $20-50/month Virtual Private Server (VPS) can comfortably handle your first 100 users.

Faster iteration: No distributed systems complexity to slow down development.

Easier debugging: All logs are in one place, and there are no network issues between components.

Full-stack visibility: You can trace every request end to end because there’s only one execution path.

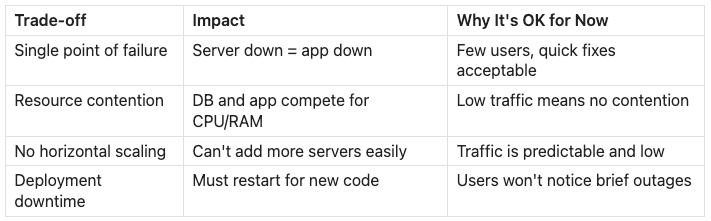

The Trade-offs You’re Making

This simplicity comes with trade-offs you accept knowingly:

When to Move On

You’ll know it’s time to evolve when you notice these signs:

Database queries slow down during peak traffic: The app and database compete for the same CPU and memory. One heavy query can drag down API latency for everyone.

Server CPU or memory consistently exceeds 70-80%: You’re approaching the limits of what a single machine can reliably handle.

Deployments require restarts and cause downtime: Even short interruptions become noticeable, and users start to complain.

A background job crash takes down the web server: Without isolation, non-user-facing work can impact the user experience.

You can’t afford even brief downtime: Your product has become critical enough that even maintenance windows stop being acceptable.

At some point, the server starts to struggle under the weight of doing everything. That’s when it’s time for your first architectural split.

Stage 2: Separate Database (100-1K Users)

As traffic grows, your single server starts struggling. The web application and database compete for the same CPU, memory, and disk I/O. A single heavy query can spike latency and slow down every API response.

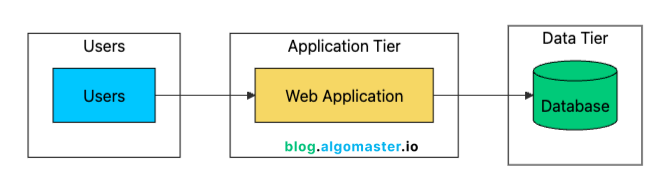

The first scaling step is simple: separate the database from the application server.

This two-tier architecture gives you several immediate benefits:

Resource Isolation: Application and database no longer compete for CPU/memory. Each can use 100% of their allocated resources.

Independent Scaling: Upgrade the database (more RAM, faster storage) without touching the app server.

Better Security: Database server can sit in a private network, not exposed to the internet.

Specialized Optimization: Tune each server for its specific workload. High CPU for app server, high I/O for database.

Backup Simplicity: Database backups don’t affect application performance since they run on a different machine.

Managed Database Services

At this stage, most teams use a managed database like Amazon RDS, Google Cloud SQL, Azure Database, or Supabase (I use Supabase at algomaster.io).

Managed services typically handle:

Automated backups (daily snapshots, point-in-time recovery)

Security patches and updates

Basic monitoring and alerts

Optional read replicas (we’ll cover these later)

Failover to standby instances

The cost difference between self-hosting and managed is usually small once you factor in engineering time. A managed PostgreSQL instance might cost $50–$100/month more than a raw VM, but it can save hours of maintenance every week. Those hours are better spent shipping features.

The main reasons to self-manage a database are:

Cost optimization at very large scale

Specific configurations that managed services don’t support

Compliance requirements that prohibit managed services

You’re building a database product

For most teams, managed services are the right choice until your database bill grows into the thousands of dollars per month.

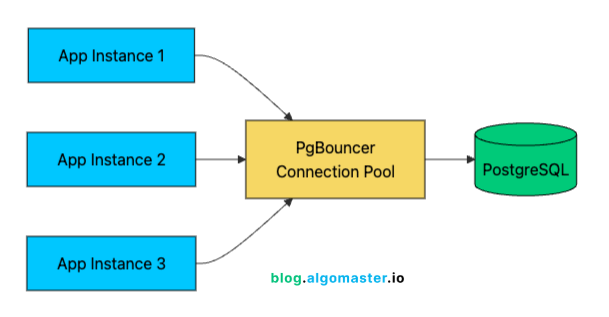

Connection Pooling

One often-overlooked improvement at this stage is connection pooling. Each database connection consumes resources:

Memory for the connection state (typically 5-10MB per connection in PostgreSQL)

File descriptors on both app and database servers

CPU overhead for connection management

Opening a new connection is expensive too. Between the TCP handshake, SSL negotiation, and database authentication, you can add 50–100 ms of overhead per request.

A connection pooler like PgBouncer (for PostgreSQL) keeps a small set of database connections open and reuses them across requests.

With 1,000 users, you might have 100 concurrent connections hitting your API. Without pooling, that’s 100 database connections consuming resources. With pooling, 20-30 actual database connections can efficiently serve those 100 application connections through connection reuse.

Connection pooling modes:

Session pooling: One pool connection per client connection (most compatible, least efficient)

Transaction pooling: Connection returned to the pool after each transaction (best balance for most apps)

Statement pooling: Connection returned after each statement (most efficient, but can break features)

Most applications work best with transaction pooling, which often improves connection efficiency by 3–5x.

Network Latency Considerations

Separating the database introduces network latency. When app and database were on the same machine, “network” latency was essentially zero (loopback interface). Now every query adds 0.1-1ms of network round-trip time.

For most applications, this is negligible. But if your code makes hundreds of database queries per request (an anti-pattern, but common), this latency adds up. The solution isn’t to put them back on the same machine, but to optimize your query patterns:

Batch queries where possible

Use JOINs instead of N+1 query patterns

Cache frequently accessed data

Use connection pooling to avoid repeated connection setup overhead

With the database on its own server, you’ve bought yourself room to grow. But you’ve also created a new single point of failure: the application server is now the weak link. What happens when it goes down, or when it simply can’t keep up with demand?