The Hidden Cost of Database Indexes

“Just add an index.”

This is the most common advice when a query runs slow. And it works. Indexes can turn a 30-second query into a 30-millisecond one.

But indexes aren’t free. Every index you create comes with costs that are easy to overlook until they become a problem.

In this article, we’ll explore the hidden costs of database indexes that every developer should understand before reaching for `CREATE INDEX`.

1. The Write Performance Penalty

When you think about indexes, you probably think about SELECT queries. But every index also affects INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE operations.

Here’s why: an index is a separate data structure (usually a B-Tree) that maintains a sorted copy of the indexed column(s) along with pointers to the actual rows. When you modify data in the table, the database must also update every index on that table.

How Each Operation is Affected

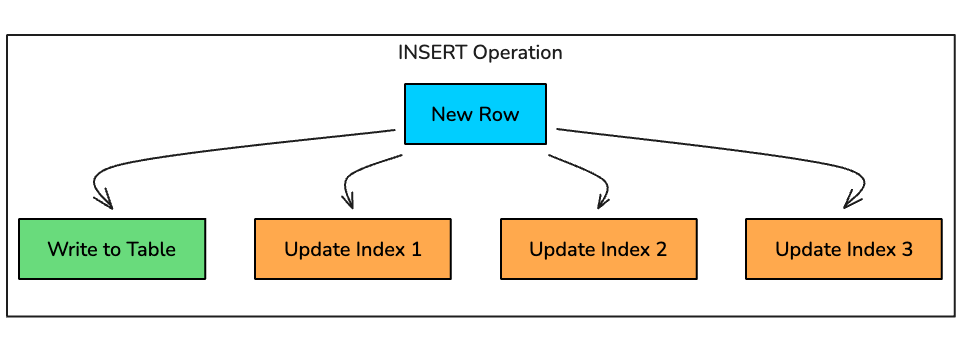

INSERT: For every new row, the database must:

Write the row to the table

Find the correct position in each B-Tree index

Insert a new entry in each index

Potentially rebalance the B-Tree if nodes split

UPDATE: When you update an indexed column, the database must:

Update the row in the table

Remove the old entry from the index

Insert a new entry at the correct position

This is essentially a DELETE + INSERT on the index

DELETE: For every deleted row, the database must:

Remove the row from the table

Find and remove the corresponding entry in each index

Potentially rebalance the B-Tree

Real-World Impact

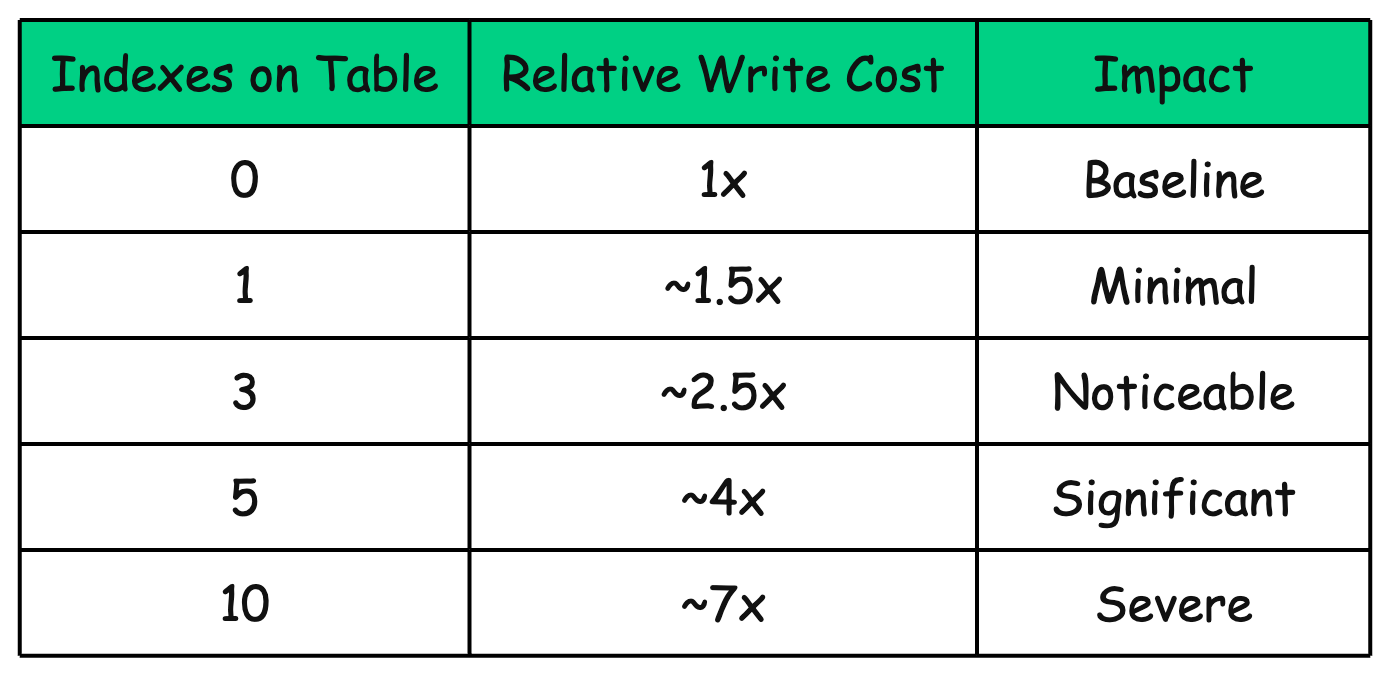

Consider a table with 5 indexes. Every INSERT now requires 6 write operations instead of 1. The overhead compounds quickly:

These numbers are approximate and depend on many factors (index type, column size, tree depth), but the trend is clear: more indexes = slower writes.

For write-heavy workloads like logging systems, event tracking, or IoT data ingestion, this overhead can become a serious bottleneck.